The Assembly of First Nations is calling on Canada’s federal government to remove regulatory barriers it says are excluding Indigenous entrepreneurs from participating in the expanding adult-use marijuana industry.

The national advocacy group’s assertion – made in an interview with MJBizDaily and in its 2021 “Federal Priorities” document – seems to be borne out in the statistics.

According to data shared with MJBizDaily, Indigenous-owned or -affiliated cannabis businesses make up less than 5% of all federal license holders.

That’s approximately the same percentage of people in Canada who identify as an Aboriginal person. However, “affiliated” is a broad term that could include any business with Indigenous investors, so the percentage of Indigenous-owned businesses is thought to be lower.

Meanwhile, 0.5% of the approximately 750 licensees are located on one of Canada’s 3,100 reservations.

“The Cannabis Act as it stands right now is failing, and these stats are indicative of some of the barriers that many First Nations are experiencing,” Terry Teegee, chair of the Chief’s Committee on Cannabis for the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), told MJBizDaily in a phone interview.

“Where we’re failing is the fact that, far too often, First Nations jurisdiction and ability to license and control cannabis, or anything in our territory, is not recognized.”

Drilling into the numbers

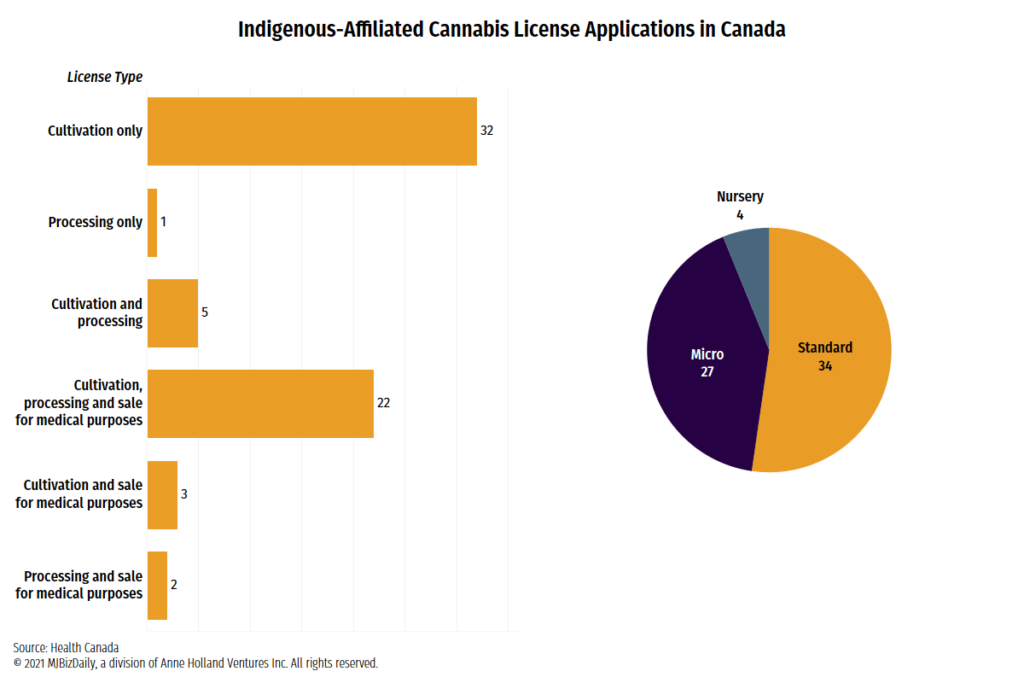

Out of the approximately 750 federal cannabis license holders in Canada, about three dozen identified as Indigenous-owned or -affiliated as of August, according to data shared by Health Canada.

One year ago, there were 19 Indigenous cannabis companies, meaning that 18 more wound their way through Health Canada’s licensing process in the past year.

Health Canada says license applicants can self-identify as Indigenous-affiliated, but there is no set criteria or percentage of Indigenous affiliation needed to qualify.

“This can include any person or persons of First Nation, Inuit and/or Métis descent or any community, corporation or business associated with a First Nation, Inuit and Métis government, organization or community,” Health Canada spokesman Andre Gagnon said via email.

He said some applicants identify key personnel as being Indigenous, while others self-identify with First Nations investment or have a plan in place to hire Indigenous employees.

“Self-identified, Indigenous-affiliated applicants are referred to a dedicated licensing professional who is knowledgeable about Indigenous priorities, communities and circumstances, and will provide ongoing support throughout the licensing process,” Gagnon said.

Indigenous licensees must meet the same eligibility requirements and criteria.

By license type, there were:

- 20 standard license holders.

- 14 micro license holders.

- 2 nursery license holders.

- 1 license to sell only medical cannabis.

AFN: Amend the Cannabis Act

The Cannabis Act, which established the legal foundation for the newly regulated industry in 2018, handed distribution and sales authority to provinces and territories, with the federal government holding on to cultivation regulation.

The law didn’t provide Canada’s First Nations the ability control production or retail on a reservation.

AFN’s Teegee, who is also the elected regional chief of the British Columbia Assembly of First Nations, wants that rectified.

What’s missing from the law is the “perspective of First Nations to recognize our inherent rights, treaty rights and our ability to govern ourselves in terms of self-determination and sovereignty,” he said.

“Quite obviously that was missed in terms of the development of the Cannabis Act.”

The law is up for a mandated review later this year, so Teegee says now is an “opportune time” to consider amendments.

The law’s impact on Indigenous people and communities is required to be part of that review.

Canada’s adoption of the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (Bill C-15) earlier this year could set the stage for the country to meaningfully incorporate reconciliation into the Cannabis Act, Teegee said.

“Here’s an opportunity to reconcile with the Indigenous people now that we have the declaration and the ability to amend the Cannabis Act,” he said.

Indigenous entrepreneurs ‘missing out’

Newfoundland-based BeeHigh Vital Elements is one of a small number of Indigenous-owned and -operated federally licensed cannabis companies in Canada.

Rita Hall, BeeHighVE’s president and CEO, said being a pioneer has come with some challenges, particularly since the company is a small craft producer.

“While other larger companies have had the benefit of operating without the same financial constraints because they are publicly traded, we continue to have to think very carefully about where our money is going next,” she told MJBizDaily.

“We have been very strategic to date, but we have never strayed from our initial business goal – to be a craft cannabis producer that is focused on bringing quality cannabis and pure NL honey products to our consumers.”

Hall, one of only a few women CEOs of a federally licensed cannabis business, also wants amendments to the Cannabis Act.

Specifically, she wants federal licensed holders such as BeeHighVE to have the ability to sell to First Nations in the same way licensed producers are authorized to sell to provinces and territories.

She said Indigenous entrepreneurs are missing out on opportunities because of the current legislation.

“Cannabis retail is one of them,” she said. “First Nations weren’t awarded this opportunity (retail) for economic development through the Act. This needs to change.”

She said First Nations could collaborate with the federal government to establish a plan that outlines how distribution and sales might work for First Nations.

Social equity

Some critics have noted that Canada did little regarding social equity when adult-use cannabis was legalized three years ago.

In some U.S. states, in contrast, business licenses are set aside exclusively for minority entrepreneurs.

In New Zealand, a Maori company received the country’s first medical cannabis business license, and various government bodies – such as the Maori Agribusiness Directorate – support Maori-run agribusiness.

Joseph Quesnel, senior research associate at the pro-business think tank Frontier Centre for Public Policy in Nova Scotia, said Canada should be doing more to accommodate Indigenous cannabis businesses.

“When it came to the consultation, it was almost universally said that First Nations, private organizations, the AFN, and a lot of representative bodies tried to get in the conversation when they were (making) the Cannabis Act,” he said.

“They wanted something, and not even priority access, but some kind of equity in terms of an equal playing field. It was universally acknowledged that First Nations didn’t get much at all from the consultation.”

Given the legalization framework implemented by Canada’s Liberal Party, Quesnel said it isn’t a surprise that less than 1% of Canada’s federal licenses have been provided to Indigenous businesses on a reservation.

“First Nations should have been involved from the beginning,” he said.

“It’s a big indigenous economic reconciliation fail on the government’s part, because they saw this coming. We were talking about cannabis legalization for a long time.

“If this government wanted to claim they were about Indigenous economic reconciliation, this is very much not the way to go about it.”

Matt Lamers is Marijuana Business Daily’s international editor, based near Toronto. He can be reached at matt.lamers@mjbizdaily.com.