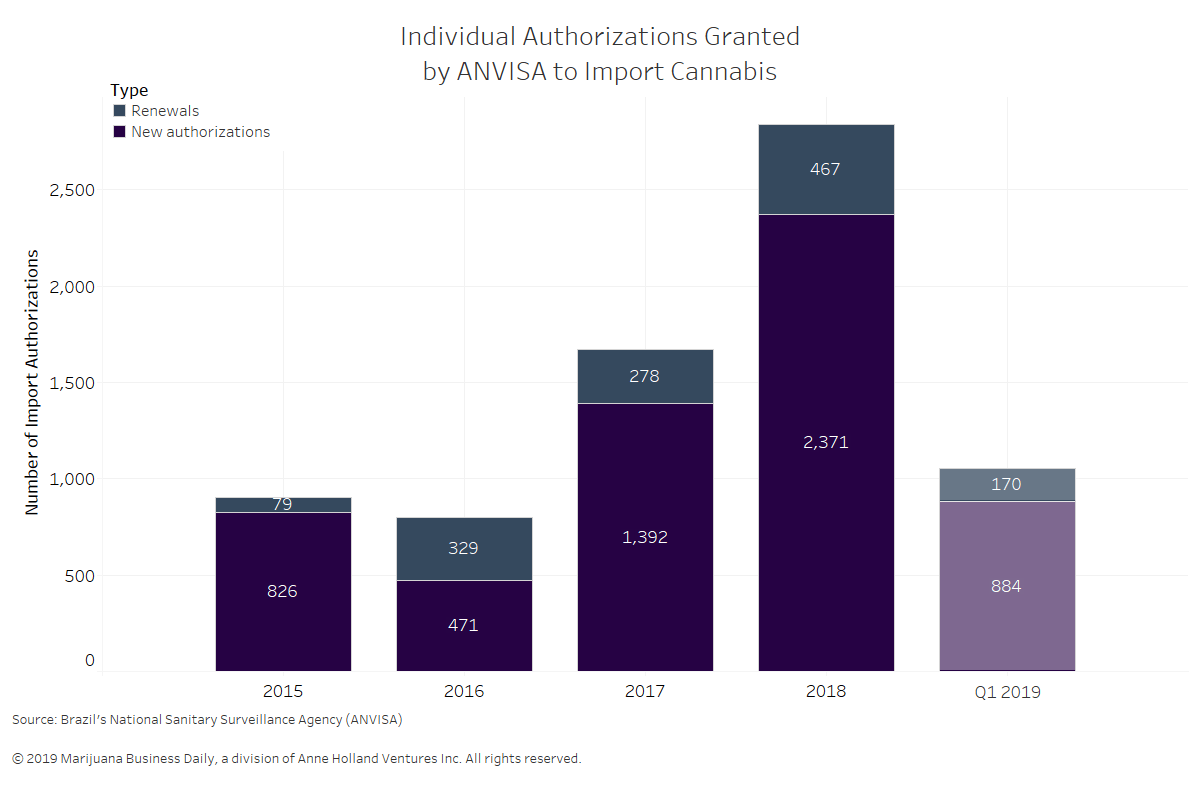

Brazilian authorities continued to approve permits to import medical cannabis at an increasing rate through the first quarter of 2019.

According to data provided to Marijuana Business Daily, Brazil’s National Sanitary Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) granted 884 new authorizations and 170 renewals during the first quarter of 2019 – more than one-third of all the authorizations that were handed out in 2018.

However, the number of new authorizations has far outstripped the number of renewals since imports began in earnest in 2015.

Leandro Stelitano, president of Cannab, a Brazilian association that supports MMJ patients, confirmed to MJBizDaily that many patients discontinue treatment after the first year because of unaffordable import prices.

But there are other potential reasons for the difference between the new authorization and renewal numbers, according to Carolina Nocetti, a Brazilian doctor who specializes in treatments with cannabis. Those reasons include:

- New applications submitted to ANVISA by patients who failed to renew their initial authorizations.

- Patients turning to legal or illegal associations or growers that provide products for a fraction of the import price.

- Individuals start growing at home, in most cases illegally.

ANVISA authorities told MJBizDaily that they don’t know the exact number of authorizations that are currently valid.

What is known is that roughly 6,000 new import authorizations were granted since the program started, but the number of permits handed out during the past 12 months is below 3,000.

Quest for cannabis access

Lack of affordability and availability has led a number of courts to rule in favor of patients seeking increased access to medical cannabis on the grounds of a constitutional right to health.

Local industry stakeholders, who requested anonymity, are concerned about a trend in which foreign companies increase sales by “incentivizing” patients to sue the government for MMJ access.

The concern comes not only from a perceived conflict of interest – as the companies stand to benefit financially from these types of court decisions – but also from the potential for significant administrative and financial challenges to the country’s system.

For example, many of the cases would require the government to reimburse patients for the cost of imported products.

“We have a very fragile regulatory framework – abuse it, and it could easily backfire,” a local source said.

Nocetti disagrees.

“If the government doesn’t want to deal with so many cases in (court), they should fix the system and provide real access to patients,” she said.

A few patients have obtained a judicial decision that allows them to grow at home, and at the end of 2017, a Brazilian court allowed one patients association to produce for its members.

A bill that would allow home-growing saw some movement in the parliament at the end of last year, without any meaningful developments since then.

New drug policy

While the number of medical cannabis patients continues to grow, the new government is taking actions to return to an abstinence-based drug policy, shying away from harm-reduction approaches.

A new decree that establishes guidelines for drug policy was signed by the president on April 11.

While the decree doesn’t seem to have any immediate impact on the existing medical cannabis program, many view the government’s move with concern.

The new harsher drug policy was supported by:

- The Federal Council of Medicine (CFM, aka Conselho Federal de Medicina), which regulates the medical profession in the country and acts as the gatekeeper that allows only certain doctors to prescribe cannabis for a limited number of conditions. Last February, the CFM issued a communication stipulating the organization opposes any legalization or decriminalization of psychoactive substances.

- The Brazilian Association of Psychiatry (ABP, aka Associação Brasileira de Psiquiatria), which celebrated the new decree the day it was signed. The ABP has campaigned with the CFM against easier access to medical cannabis. Antonio Geraldo Da Silva, former president of the ABP and current president of the Latin American Psychiatric Association, said in 2016, that “there is no medical marijuana.”

Leonardo Sérvio Luz, the youngest counselor of the CFM, representing the state of Piauí, said at a March congress that the organization “can’t act according to a wish” in allowing MMJ use since it’s not an evidence-based medicine.

Alfredo Pascual can be reached at alfredop@mjbizdaily.com