For the third time in less than four years, California lawmakers are revisiting the state’s marijuana licensing program, ostensibly to give businesses and regulators more time to get permits processed while allowing the industry to keep functioning without major interruption.

In the balance hangs the possible fate of more than 8,000 marijuana business licenses, including retailers, growers and other companies that are still operating on business permits that were originally crafted by the state to be temporary, not permanent.

“The regulated industry in California would be at significant risk of potential collapse” if the issue isn’t fixed by lawmakers, warned Genine Coleman, executive director of the Origins Council in Mendocino County.

At issue is the state marijuana “provisional” licensing program, which California created toward the end of 2018 as a stopgap measure to give entrepreneurs more time to transition from “temporary” business licenses to full “annual” permits.

But the bill that established the provisional licenses gave the program only a one-year life span.

Then, in 2019, lawmakers reauthorized the program, this time with a two-year window.

One of the biggest bottlenecks delaying the issuance of annual permits is a state law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), that every business in California – marijuana included – must comply with.

The amount of time needed to prove compliance with that law has helped create the current backlog of thousands of businesses that are still operating without full annual licenses.

A key sticking point: Cannabis regulators don’t currently have the legal authority to issue more provisional permits – or renew existing ones – after Dec. 31, 2021.

Unless lawmakers again extend the stopgap program, thousands of companies could be forced to shut down, at least temporarily.

An industrywide hurdle

The problem affects all sectors of the state’s marijuana industry, Coleman noted, including retailers, growers, manufacturers and every other state-licensed MJ vertical.

Any business that doesn’t yet have a full annual license is at risk if an extension isn’t approved.

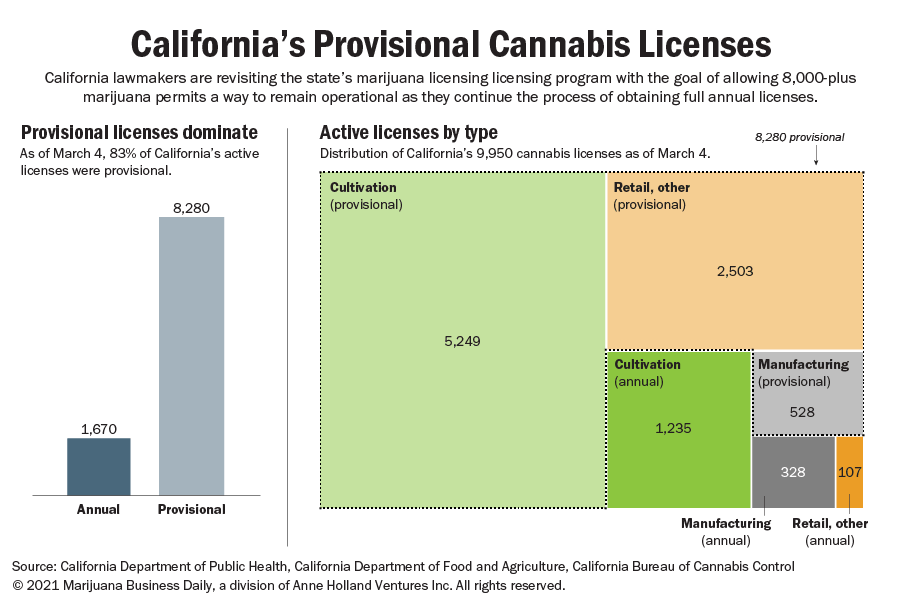

As of March 4, a whopping 83% of marijuana business licenses in California were active provisional permits, while only 17% were annual licenses. That’s out of a total 9,950 permits.

“Because it’s sectorwide and regionwide and impacts every part of the supply chain, it could be really significant damage,” Coleman said.

Enter Senate Bill 59. Introduced by state Sen. Anna Caballero, the legislation is intended to fix the provisional issue by extending the program for an additional six years, until Jan. 1, 2028. The bill is slated to be heard by the state Senate Business, Professions and Economic Development Committee on April 5.

If history is any guide, the bill likely will pass easily. But nothing is easy for the California cannabis industry.

Environmental politics at play

Underpinning the provisional license crisis is the CEQA, with which every cannabis company must show full compliance in order to win an annual license.

And compliance can be broad, depending on the business and its actual operations – outdoor cultivators, for instance, will all likely have to ensure their operations have no impact on nearby water sources.

The issue: Compliance takes months – if not a year or more – for every company. And businesses often must meet both local- and state-level mandates.

Also, the entire process can be extremely costly, sometimes running six figures for businesses.

Which is why one industry attorney in 2019 predicted the CEQA would become a “silent killer” for marijuana companies.

The time-consuming compliance steps are the reason the provisional licensing program was created.

Regulators and industry officials realized it wasn’t reasonable to expect the entire industry to rocket through the compliance process to obtain annual licenses within a year – or even two.

Amy Jenkins, the lead lobbyist for the California Cannabis Industry Association, warned that businesses should contact their lawmakers to voice support for SB 59 to ensure it passes the Legislature this year.

“Right now, the assumption is this will just get approved and that this is an easy process, and in fact, it is not,” she said.

Jenkins said the environmental lobby in particular has “considerable concerns” that most of the marijuana industry has not formally complied with the environmental protection law.

“We’re in an uphill battle to convince the environmental community” that most of the marijuana industry isn’t deliberately sidestepping the CEQA, she said.

That could endanger the passage of SB 59.

Kristin Nevedal, the executive director of the Humboldt County-based International Cannabis Farmers Association, echoed Jenkins’ concerns.

Nevedal said she’s worried too many marijuana stakeholders are pinning their hopes on a last-minute fix by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Alternatively, they might be waiting for a more comprehensive reform bill that would address the cumbersome nature of the environmental protection law itself, which various California industries have long viewed as an albatross because of the amount of red tape associated with it.

“The groundswell of support for extending provisional licenses needs to happen now, not to wait for amendments or to wait to see if CEQA could be fixed or wait to see if the governor is going to rescue the industry,” Nevedal said.

“Even if you have an annual license, the thought that you could lose (83%) of your supply-chain capacity should be horrifying folks.”

More ripple effects

The issue isn’t only at the state level.

In Mendocino County, for example, one of three counties that comprise California’s famed Emerald Triangle, hundreds of farmers are awaiting the outcome of a new CEQA-related ordinance that the county Board of Supervisors is working on.

That’s mainly because the county adopted a CEQA compliance program for its marijuana farmers before the state Department of Food and Agriculture issued its own requirements for cannabis companies.

That meant that the local ordinance was “out of sync” with what the state required, said Patrick Sellers, board chair of the Mendocino Cannabis Alliance.

Mendocino isn’t alone in having to shift its CEQA and cannabis industry-related regulations, Sellers said. The same has been happening in a number of cities and counties statewide.

“None of it’s really working, and all of it’s taking a long time,” Sellers said. “Hence the need for the provisional licensing program to be extended, because the extension that was given previously has allowed some jurisdictions to make some progress.”

Sellers also warned that without the success of SB 59, “a lapse in continuity for licensure for these (marijuana farmers) puts them out of business.”

In the meantime, the 83% of the businesses still operating on provisional licenses are doing so without much legal protection, since state regulators view provisional licenses as temporary.

That point was driven home in recent weeks by an ongoing legal battle between state officials and Hayward-based Harrens Lab.

The state Bureau of Cannabis Control (BCC) revoked Harrens’ provisional business license on Feb. 4 and forced it to cease operations.

The BCC also informed the lab that because it was operating on a provisional permit, it had no right under state law to an appeals process. That meant Harrens’ only recourse to regain its license was through the courts.

So the lab sued and quickly won a temporary reprieve from a Superior Court judge, who ruled that the lab could reopen for business until the larger due-process question could be settled.

But that question – whether provisional license holders have any right to appeal a license revocation – remains an open one.

California Attorney General Xavier Becerra has already asserted, on behalf of the BCC, that provisional license holders have no right to due process.

The case is ongoing – a hearing is scheduled for March 25 – but it stands as a reminder to other provisional license holders that their ability to do business could be jeopardized if they don’t maintain strict compliance with all state rules.

John Schroyer can be reached at john.schroyer@mjbizdaily.com.