Cannabis growers, manufacturers and retailers planning to build new facilities or expand existing ones are facing not only soaring costs for materials but also lengthy wait times to get their projects off the ground.

And it’s not just the global COVID-19 pandemic that’s causing the increased cost and supply shortage for both marijuana and mainstream businesses, said David Fettner, principal of Highwood, Illinois-based Grow America Builders, a construction company serving the cannabis industry.

It became more difficult to procure insulation after temperatures plummeted in February in Texas, which is among the top producers and distributors of building materials nationwide.

When the Suez Canal was blocked for six days in March after the grounding of the massive Ever Given container ship, all sorts of building materials became even more difficult to get.

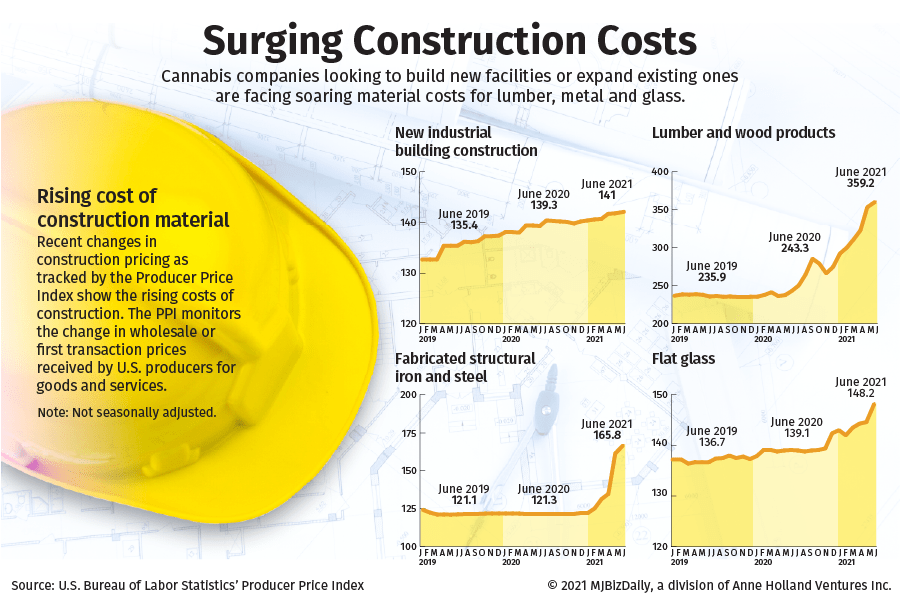

Wholesale steel prices, for example, rose 36% during the first six months of the year, according to federal data. Lumber prices in June were up 23% from January and 48% from June 2020.

“A lot of construction components are a hot commodity right now,” Fettner said. “Luckily, we’ve stockpiled, so it’s so far, so good on our end.”

Fettner estimates the cost of some building materials has gone up as much as 40% over the past year.

Most facilities for cannabis businesses are built using metal stud construction, and the cost of metal studs has gone up 15% to 20% during that time, Fettner said.

“Cost is an issue, but the availability is really what we have red-flagged,” Fettner said.

“When you’re building anything in the cannabis industry, time is of the essence. When we see an item that’s typically in stock but is now eight weeks out, we stockpile.”

Most of the cultivation facilities that St. Louis-based Arco National Construction builds for its cannabis clients are preengineered metal buildings.

Even with the cost of steel up by as much as 40% in the past 12 months, the building material is in short supply, said Drew Blaylock, Arco’s director of preconstruction.

No delays

Even so, cannabis companies are not delaying construction projects in the hopes that the costs eventually will come down.

Regulatory issues often drive those decisions because some states set deadlines to have cannabis businesses operational or risk losing their licenses.

“A lot of them are moving forward because they have licensure requirements,” Blaylock said. “A lot can ask for extensions, but not a lot are granted extensions.”

Jon Marshall, chief operating officer of vertically integrated cannabis company Deep Roots Harvest in Las Vegas, said that while the state likely understands the difficulty marijuana businesses are facing with the escalating cost and shortage of construction materials, he’s unwilling to risk revocation of the licenses for the four facilities he’s building.

“They don’t want to see people sit on their hands for two years while they wait for environmental conditions to change,” Marshall said. “They want to see progress toward that end goal.”

To ensure it has building materials when it needs them, Deep Roots Harvest is debating ordering in bulk and committing capital sooner than it otherwise would have done so.

Blaylock said Arco, a design-build firm, will pay a premium to get materials and defer other costs to ensure it meets the established budget.

If the price of materials is pushing the cost of the project over budget and a cannabis business is required to be operating by a certain time, that company can choose either to build a smaller facility or not finish some of the rooms that were planned, Blaylock said.

“You’ve got to think outside the box,” Blaylock said.

“You have to find more creative ways to get there whether that’s through value engineering or changing your design to what you need – not what you want.

“Tell me what you must have and what you’d like to have, and we’ll come up with the best mousetrap we can design.”

Keeping a lid on costs

To keep costs down, Blaylock recommends getting the contractor involved in the project as soon as possible so that someone who has a good sense of the process and cost of materials and labor can help guide decisions and find creative ways to engineer the structural system.

With higher construction costs comes the need for a lender that can bridge the financing gap from the time construction starts until the marijuana business is actually generating revenue.

That’s where Pelorus Equity Group can help.

The Newport Beach, California-based real estate investment trust (REIT) was formed in 2010 to provide specialist finance in value-add real estate. It entered the cannabis real estate lending market in 2016. Companies can use the money to bankroll construction.

The REIT has placed more than $1 billion in capital and completed 5,000-plus value-add real estate transactions in the cannabis industry.

Pelorus will consider transactions in any state that is licensed, said the company’s president, Rob Sechrist.

“What we’re trying to solve for is when a cannabis-use tenant wants to come into a property, but the tenant doesn’t have income coming in and doesn’t have the $1 million budget it takes to build that property out,” he said.

“We’re trying to solve for making sure a tenant doesn’t have to use cash – they should be saving that gun power until they start generating revenue.”

Non-cannabis tenants pay $50-$100 a square foot for tenant improvements (TI), but a cannabis business will pay $150-$250 per square foot because it will generate up to 15 times more revenue per month than the non-cannabis tenant, Sechrist noted.

“If your TI was going to be $5 million and you haven’t generated profit yet, it would be costly to raise that,” he said. “You would have to sell part of your company, and it would be the most expensive capital you’ll ever raise.”

Fixed-cost guarantee

With the cost of materials being what it is these days, Sechrist recommends locking in a fixed-cost guarantee – even if it means paying slightly more for the project.

That way, if the cost of materials increases or there is a change order, the business is protected from paying more than it budgeted, Sechrist said.

Otherwise, contractors will write into the budget that they have the ability to surcharge. If the price is locked in, the contractor has to eat the difference.

“When you’re trying to understand what your costs are, you want to lock down as many things as possible – a surcharge would be part of the negotiation,” Sechrist said.

“You need to lock it down, because you can’t afford surprises. We can’t afford for our borrowers to have that open-endedness.”