(This story has been updated to reflect that John Nores no longer is with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.)

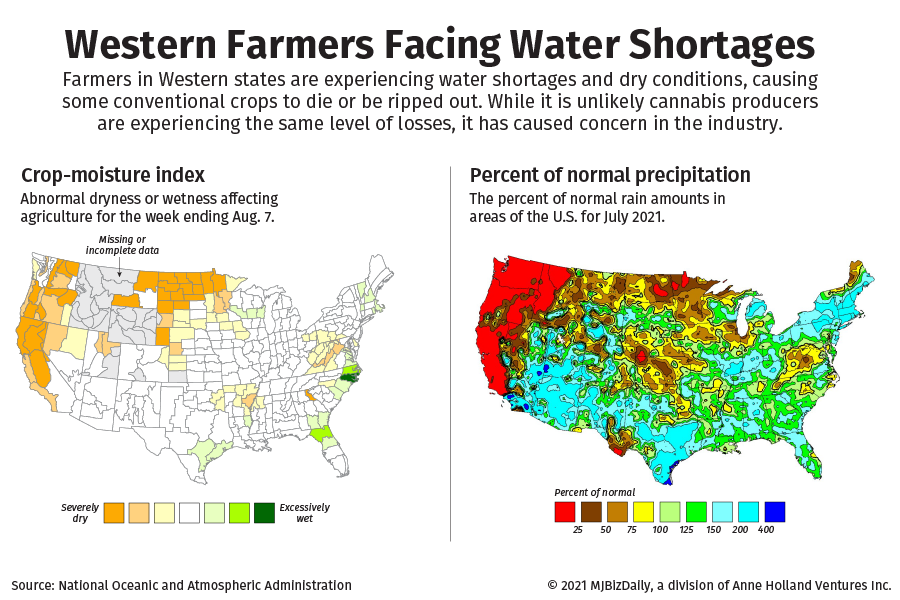

Cannabis growers in the American West haven’t escaped the massive water shortages this year that have forced farmers growing crops such as almonds and blueberries to rip out plants or let them die in the field.

The drought is depressing hemp acreage and worsening reports of water theft by illicit marijuana growers.

“It’s just a hot mess out there, to put it mildly,” said John Nores, a former official with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, who told MJBizDaily that water theft in his state this year has never been so severe.

“These outdoor trespass grows on the West Coast are anywhere from 2,000 to 20,000 plants; they leave a huge environmental footprint on public lands and right at the edge of headwaters, the pristine waterways,” he said.

Water-use studies

Cannabis farms have long had a reputation for being especially “thirsty.”

But findings from a recent study from the University of California, Berkeley’s Cannabis Research Center show that licensed cannabis growers are using less water than regulators thought.

The center, which began researching water use on cannabis farms in 2017, has used data from producers’ water-use reports, along with anonymous surveys.

Based on the average size of a Humboldt County cannabis farm and comparisons to how other agricultural commodities and specialty crops use water, Natalynne DeLapp, executive director of the Humboldt County Growers Alliance in California, said cannabis is “by far the most water-efficient agricultural product in California.”

She estimates that a single large almond farm in the Central Valley uses 33 times more water than all licensed Humboldt County cannabis farms combined, for example.

With drought and water use an ongoing concern in California, DeLapp said cannabis producers are planning for water storage and improved water-efficiency measures.

Other universities are looking at water use, as well, including a study coordinated by Oregon State University’s Global Hemp Innovation Center using drip-irrigation trials in California, Colorado and Oregon.

The studies are set up to determine water use for CBD production under different irrigation regimes and comparing crop responses to 40% to 100% of estimated water requirements, observed across five sites with different soils and climates.

Securing water rights

As the drought intensifies, regulators are reducing water availability to communities, including farms.

Some farmers are finding that selling water rights is more profitable than farming this year, said Mike Lewis, an organic farmer in Kentucky and president of the Hemp Industries Association.

He said that in northern parts of California, where 35% of all crops have not been planted this year because of the water shortage, farmers are being incentivized to sell their water rights.

It will be critical for cannabis producers to secure water rights, said Christopher Strunk, a partner at Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani in Cleveland.

But because marijuana and hemp growers often have no history of water use on newly acquired or repurposed land, that could be difficult, Strunk said last month at the AmericanHort Hemp Conference in Columbus, Ohio.

According to Nores, water rights aren’t a free-for-all, meaning growers can’t deplete a natural source just because it happens to be on their land, because wildlife, agricultural operations and municipalities might also depend on that source.

“Diverting water from a creek, a stream (or) a river is going to be analyzed, permitted and allowed very carefully.”

Opposite problem out East

While farmers in the West struggle to find enough water, cannabis producers in the East are having the opposite problem – too much rain and moisture, Lewis said.

Hemp farmers from Kentucky to Florida and across the Midwest have experienced an overabundance of moisture this summer, causing crop growth to stagnate and diseases to spread.

“My region is just covered in rain,” Lewis said.

“We have disease and pest pressures, and the plants are changing to adapt, which changes the THC threshold and the cannabinoid profiles.”

Ongoing variability and extreme weather patterns from one end of the country to the other could ultimately cause shifts in the agricultural landscape, Lewis said.

As nascent industries such as marijuana and hemp mature, weather patterns and variety performance will likely lead to regionalization for different types of cannabis production – and perhaps other agricultural crops, too, according to Lewis.

“It’s part of the reality we have to face … we shouldn’t be producing water-intensive crops in places where we’re having massive water shortages,” he said.

Nores agrees, saying it’s in the country’s best interest to “lighten the load” for agricultural regions such as the West by potentially regionalizing cannabis and other agricultural crops.

“We might have to live with that, especially if the West Coast continues to see drought after drought after drought.”

Big hit to hemp

The water shortages are contributing to falling hemp acreage nationwide, as farmers look to crops with less price volatility.

National hemp acreage for 2021 could be down significantly from last year, according to early analysis of licensed acreage.

In late June, Hemp Benchmarks counted 107,702 acres registered for outdoor production in 27 states.

That partial analysis suggests big acreage declines from 2020, when Hemp Industry Daily counted 465,787 outdoor acres in 47 states

A lack of water is certainly contributing to growers planting fewer hemp crops in the West, Lewis said.

“We’re starting to get a glimpse of what the new normal is going to be like in terms of our weather patterns right now. It’s absolutely affecting cannabis; it’s affecting all crops,” he said.

“Not only are we going to see crops not getting produced because the farmers can’t get water rights or don’t have enough water for the crops to grow effectively.”

But Matt Cyrus, a farmer in Sisters, Oregon, who elected not to plant hemp in 2021, said cannabis thrives in hot, dry conditions.

“Our experience is hemp uses about a third as much water as a hay crop,” said Cyrus, who served as president of the Deschutes County Farm Bureau.

Laura Drotleff can be reached at laura.drotleff@hempindustrydaily.com.