In a marijuana industry landscape increasingly dominated by big companies, there remains a place for small, craft cannabis producers selling high-end products ranging from flower to edibles.

In fact, if the industry evolves under the right conditions, small marijuana business advocates say, craft will be the future of cannabis. But under the wrong conditions, they warn, craft will die, leaving the industry to a handful of large, multistate marijuana companies.

“Right now, we are in danger of rushing into implementation of this large industry so quickly and in such a way that it crushes the craft industry that does exist. That is the main danger … that it will get crushed,” said Adam Smith, president of the Craft Cannabis Alliance (CCA) in Oregon.

Averting that type of future is possible but will require lots of work and savvy on the part of small marijuana businesses. Small companies that want to survive and credibly brand their products as craft cannabis will need to:

- Compose a compelling message about their brands.

- Be persistent and creative in relaying that message to retailers and consumers.

- Consider co-ops, partnerships and other avenues to reduce costs.

What Is Craft?

To survive as a craft business, it helps to understand how cannabis industry observers define “craft.” Generally, it comes down to a set of factors:

Locally connected: The business is majority owned by locals. It also sources its inputs locally, produces locally and employs locals.

Small batch: The business produces a smaller amount of product compared to larger competitors. But exact numbers haven’t been defined.

Values driven: The business emphasizes values—such as compensating employees well and contributing to the community—and puts them ahead of the bottom line.

Sustainable cultivation: The business uses only organic or natural products and environmentally friendly methods.

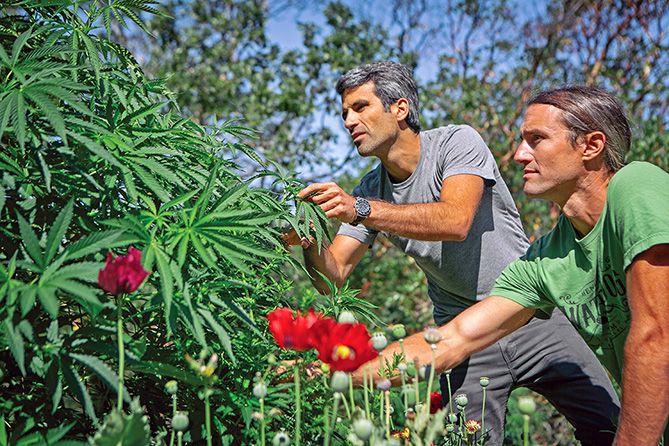

Artisanal methods: Growers, processors and other employees are able to spend time with individual plants and products to give them personal care that plants and products in bigger operations don’t get.

“A craft product is something that is sourced with intention, that has a connection to the community that it’s produced in, whether that’s through the sourcing of ingredients or paying homage, respect and tribute to the culture where the facility is in,” said Bryce Berryessa, CEO of La Vida Verde, a craft infused product company in Santa Cruz, California.

La Vida Verde has a 5,000-square-foot grow, and it sources additional cannabis and organic ingredients from other craft businesses in Santa Cruz County, Berryessa said. “It’s done in smaller batches and has more of an artisanal feel to it.”

While there are important details that make a business craft, for Smith it boils down to connection to place and being values driven.

“Connection to place is very important,” Smith said, noting that to meet the CCA’s craft criteria, a business must be majority locally owned. “And if you are values driven, it’s pretty certain that you are also making the best cannabis products you can possibly make.”

Smith said those values include ethical business and employment practices, environmental sustainability, positive community engagement and standing up to end the war on drugs.

The size of the grow and whether it’s cultivated outside, in a greenhouse or indoors are also factors that define craft.

Most craft observers seem to agree that grows that are less than 5,000 or 10,000 square feet can be considered craft. But being small does not inherently make cannabis craft. Craft is about the lead grower being able to devote time to the well-being of each individual plant, which is far easier in small grows and gets more difficult as the size of the canopy increases.

“Small size allows our head grower to spend more time with the individual plants and really pay attention to detail,” said Brandon Pollock, the CEO of Theory Wellness in Massachusetts, which has a 5,000-square-foot canopy and casts itself as a craft cannabis purveyor. In other words, if you can’t examine every individual plant in your grow in a reasonable amount of time, you’re not growing craft cannabis.

There’s more of a divide on the indoor-outdoor issue.

“I’ve heard indoor cultivators use the word craft, but it’s much harder to make that argument,” said Michael Steinmetz, CEO of Flow Kana, a California cannabis company that works with about 200 craft growers in Northern California and sells their crop to retailers. “When it comes to indoor, you can do it at small scale, with love and intention, and call it craft. And a lot of people do it. But for me, indoor is a cultural phenomenon that is left over from the prohibition.

“All of our farmers are totally outdoors, using natural elements, using the soil from the ground, regenerative practices,” he explained. “That’s very important.”

Another often-cited element of craft is selecting genetics that may not be as commercially lucrative—for example, they may produce smaller yields or take a couple of weeks longer to harvest—as more mainstream strains. As an example, Pollock cited the strain Triangle Mints.

“You can harvest at Week Eight. But if you harvest at Week 10, you’re getting a much better flower,” he said. “It takes longer, but it’s worth it, in our view.”

Also: Hand-trim only, no machine-trim.

The Science of Pricing

Craft’s appeal to consumers is understandable—higher-quality products produced by a local whose story enhances the experience. But it also costs significantly more to produce craft products, making it harder for these smaller companies to stay in business.

To offset the higher production costs, one obvious and justifiable answer—one that’s reasonable to many consumers— is for craft cultivators and manufacturers to charge higher prices. And just as there are consumers who prefer shopping at farmers markets and favor the local stores over chains, there will always be demand for craft cannabis, Berryessa said.

But after recreational legalization in California, consumers saw prices at their local retailers increase by 35%-50%, undercutting brand loyalty, Berryessa said.

What does that mean in terms of charging premium prices to offset costs?

“You can’t right now. The next two years are all about survival,” Berryessa said. “And because there are 6,000-plus manufacturers and cultivators fighting for less than 800 stores (in California), it doesn’t matter how good your product is or how great you think your processes are. If you’re priced higher than something of a similar quality that isn’t produced at the same costs, you’re not going to get any more money for it at the retailer. Right now, it’s a margins game, a survival game. And because consumers don’t have a lot of brand loyalty, and it’s more about value, it’s a challenge.”

In mature markets, meanwhile, charging premium prices as a way to distinguish yourself is a necessity, said Daniel Sloat, president and head grower at AlpinStash, a craft grow in Colorado.

“Craft people have been somewhat insulated from the downward pricing trend because we are craft and small batch,” Sloat said. “It’s necessary to our survival to offer a craft product, because if we were just growing mediocre-quality cannabis with salt-based nutrients, we couldn’t compete.”

Crafting a Message

A key to craft success is creating a compelling message that resonates with retailers and consumers and then relaying it effectively through available channels, such as packaging, social media, alternative newspapers and the company’s own salespeople.

To convey its craft brand, La Vida Verde stresses locale. “We put that on the package that all the cannabis and the ingredients are sourced from Santa Cruz County. When you buy one of our pre-rolls, the packaging will say, ‘Cultivated in Santa Cruz County,’” Berryessa said.

La Vida Verde’s marketing efforts mostly come from in-house staffers, but the company also works with outside professionals who help with creating content, graphics and photography.

Getting product onto retail shelves also requires persistence and a personal touch in a day and age when retailers are flooded with marketing calls from product suppliers. Sloat from Colorado-based AlpinStash said he and his business-partner wife would drop off samples, but that turned out to be a waste of time and product, because budtenders would just dump the samples in a big box with others.

The couple didn’t stop with the samples, however. Rather than just dropping off samples, they’d request to spend a few minutes with a purchasing manager, just enough time to tell their story and talk up their product.

According to Sloat, no meeting means no samples.

“Then, we can talk about ourselves while the product is in front of them,” he said. “We only drop off samples if we know we can meet with the purchasing manager and establish that connection and present our story and brand narrative.”