(Editor’s note: This column is part of a recurring series of commentaries from professionals focused on the cannabis industry. Allison Justice is founder and CEO of The Hemp Mine, a South Carolina-based vertically integrated hemp company. In addition to farming 30 acres, The Hemp Mine supplies hemp young plants bred in-house across the U.S.)

(Editor’s note: This column is part of a recurring series of commentaries from professionals focused on the cannabis industry. Allison Justice is founder and CEO of The Hemp Mine, a South Carolina-based vertically integrated hemp company. In addition to farming 30 acres, The Hemp Mine supplies hemp young plants bred in-house across the U.S.)

Traditionally when growing cannabis, the thought is to simply apply over 18 hours of light per day to keep plants vegetative and switch to 12 hours to induce flowering.

This works, so why change it?

As cultivation of outdoor cannabis spreads across the U.S., understanding how cannabis responds to light becomes very evident.

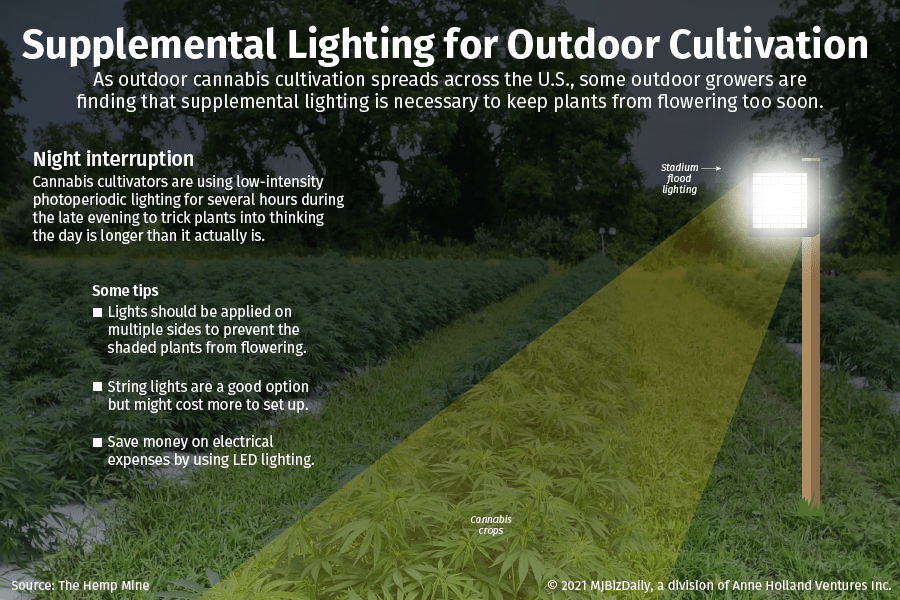

Some growers are finding out that supplemental lighting is necessary even with outdoor grows.

Photoperiodism

Let’s back up a minute and make sure we are on the same page.

What is photoperiod? It is a physiological change based off night length.

So, even though we think and speak of photoperiod as daylight hours, that isn’t quite correct.

For example, if you were to turn your grow lights on for only five minutes in the middle of the 12-hour dark cycle, your plants will stay vegetative.

How cool is that? Cannabis, poinsettias and garden mums are all “short-day” crops. This means that under short days (aka long nights), the plant will become reproductive.

Below you see a typical indoor schedule for growing cannabis.

Vegetative propagation takes around two weeks. The vegetative cycle can be anything from 1-10 weeks (all depending how big you want your finished plant to be; typical is three weeks), and flowering can last 8-12 weeks, depending on the cultivar.

This works perfectly well and is easily achievable for multiple harvests per year. Once you move outside, things get a little trickier.

Cannabis crop schedules

When growing outdoors, natural day length never extends longer than 18 hours. Most areas get under 12 hours per day in the winter months.

For the states early to adopt cannabis cultivation (Washington, Colorado, Oregon), breeding began for those regions.

2020 was the first year (in modern history) that hemp was grown commercially below the 30th parallel – which includes Hawaii and parts of south Texas and Louisiana and Florida.

The cultivars bred to produce in northern climates with long summer days did not always translate well when grown in southern latitudes with very different photoperiods.

To visualize the daylength difference, let’s consider two very different regions of the U.S. – Lansing, Michigan, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Midsummer days in Lansing can be more than two hours longer than midsummer days in Baton Rouge. Neither location drops below 12 hours of sunlight between mid-March and mid-September.

Does that mean cannabis will not flower outside in these locations? No.

Using the usual critical photoperiod for commercial hemp varieties (14 hours,10 minutes), Lansing has approximately seven weeks with daylight hours long enough for the plant to stay vegetative.

On the other hand, in Baton Rouge, the plants potentially could stay vegetative for one to two weeks. Though the farmer is paying the same amount per seed or liner, the yield will be devastatingly different.

Varieties are critical

If we know our varieties more intimately, we can be suited for success.

That makes it crucial for outdoor cannabis producers to choose the right variety.

In variety trials, we’ve found that that some varieties tolerate shorter summertime days, giving the farmer a longer vegetative cycle.

However, a farmer must beware that substituting this same plant in a region does significantly shift the flower initiation date later – meaning a later harvest.

For northern regions, this could mean a frost before the flowers are mature.

A map produced last year by plant breeders and the University of Tennessee gives farmers a guide to understand daylength and the dangers of frost for planting and harvest.

Now we understand why certain varieties perform differently at varying latitudes. But how can we manipulate that in a cost-effective way?

It does not take much light to keep plants vegetative.

For example, poinsettia and other short day crops require very little light.

This light can be applied at the beginning or end of the day’s natural light or to achieve night interruption.

Night interruption is the practice of providing low-intensity lighting to plants during the middle of the night.

By interrupting the dark period, the plant will think it’s a long day. This is typically done in the middle of the night (i.e., from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m.). This can be achieved easily with stadium or flood lights on multiple sides of the field.

It is important to remember lights will need to be applied from multiple sides. That’s because the side that doesn’t receive direct light can still flower.

String lights are also a good option – though more costly in a field setting because of the necessary light count plus the need for a structure to hold the lights. LEDs are a great option for electrical savings.

Semi-autoflower

Though ”autoflower” is misleading horticulturally, in the cannabis industry, the terminology works. These plants are not autoflowers (aka day neutral) at all.

Rather, they are photoperiodic with a flowering response time greater than 17 hours of light per day.

When grown outdoors in the continental U.S., they will flower because daylength will not go over 16 hours.

At first, this might seem like a variety that can be grown only indoors.

In fact, understanding how we can manipulate these plants with light provides a whole new way of growing, with the potential to have many crops per season.

In this photo of supplemental lighting on a half-acre plot in South Carolina, you’ll notice one 300-watt LED light on a telephone poll lining the field.

Whereas these varieties would typically flower immediately after transplant, because of the photoperiodic lighting, we were able to grow these plants to a size that will produce a profitable yield.

What else does this mean? In warmer climates, we can run multiple cycles per year without the need of a greenhouse or blackout cloth.

Additionally, as true “autoflower” varieties (which are available only via seed) are still being optimized through breeding, this is a great way to optimize clones and have a profitable harvest with consistency and size.

The more we know, the better we grow!

Allison Justice can be reached at allison@thehempmine.com.

The previous installment of this series is available here.

To be considered for publication as a guest columnist, please submit your request here by filling out our form.