Last week’s meteoric rise of GameStop’s shares made headlines, but what should be made of it? And what can we learn from it for marijuana?

What happened with GameStop is a short squeeze. The same thing happened to Tilray in 2018, Volkswagen in 2008 and supermarket operator Piggly Wiggly in the 1920s.

While it is possible to profitably invest by selling whatever is rising at ever-higher prices for nonfundamental reasons, it is a tough zero-sum game where, by definition, someone must eventually lose.

Even the winner eventually loses as well when its trading counterparts run out of money or, as happened at Piggly Wiggly, when someone more powerful changes the rules of the game for their own benefit.

Over the long term, we at MJResearchCo believe the highest and most reliable source of returns comes from the core function of capital markets – matching those who have more ideas than capital with those who have excess capital for a mutually beneficial deployment of capital at higher returns.

We focus on the fundamentals because that is what will drive true value creation over time in what we think is the most interesting secular growth theme of the next decade: legal cannabis.

But this does not mean we ignore price moves. You always need situational awareness to know when the game changes.

If you’re playing basketball with your friends, and 11 strangers in helmets and shoulder pads line up at half court, you need to realize you’re not playing basketball anymore and adjust your strategy.

If you continue to shoot three-pointers, you’re going to get tackled.

Fundamentals versus market mechanics: weighing versus voting

In Berkshire Hathaway’s 1993 investor letter, Warren Buffett quoted his mentor, Ben Graham:

“In the short run, the market is a voting machine – reflecting a voter-registration test that requires only money, not intelligence or emotional stability – but in the long run, the market is a weighing machine.”

This is why opportunities to buy good companies at cheap prices exist. The “voting” of the market sells down something to below the value supported by fundamentals.

Over the short term, the value of a company is driven by whatever the last person wanted to pay for one share – and that can be for many reasons that have nothing to do with the fundamentals.

Unlike Buffett, we don’t bother judging the “intelligence” or “emotional stability” of the other side’s reasons.

Over the long term, the most solid support of a stock price is the fundamental profitability of the underlying business – the “weighing.”

If you can’t sell the stock (for example, because the public markets shut down or the company was private), the only return comes from the cash distributed to the equity owners in the form of dividends or share repurchases.

The best investors keep an eye on both the long-term fundamental “weighing” perspective and the near-term price moves from the “voting” perspective, and they buy good companies at low prices when the two diverge.

Companies weigh in with new capital issuance

Smart companies should have an idea of their own intrinsic worth and potential returns on existing and potential projects.

If the market bids up their stock, companies will issue new stock at high prices to fund those high-return projects.

In an ideal world, GameStop would sell as much new stock as it can after a tenfold increase in its market capitalization – which, ironically, would let them better fight their secular headwinds. But market dynamics probably prevent this.

Though not currently in a squeeze, cannabis stocks have traded up double digits (an average of 19% for U.S. operators and 55% on average for Canadian operators) after the Jan. 5 “blue wave” of Democrats’ wins in Georgia and Aphria’s better-than-expected earnings report.

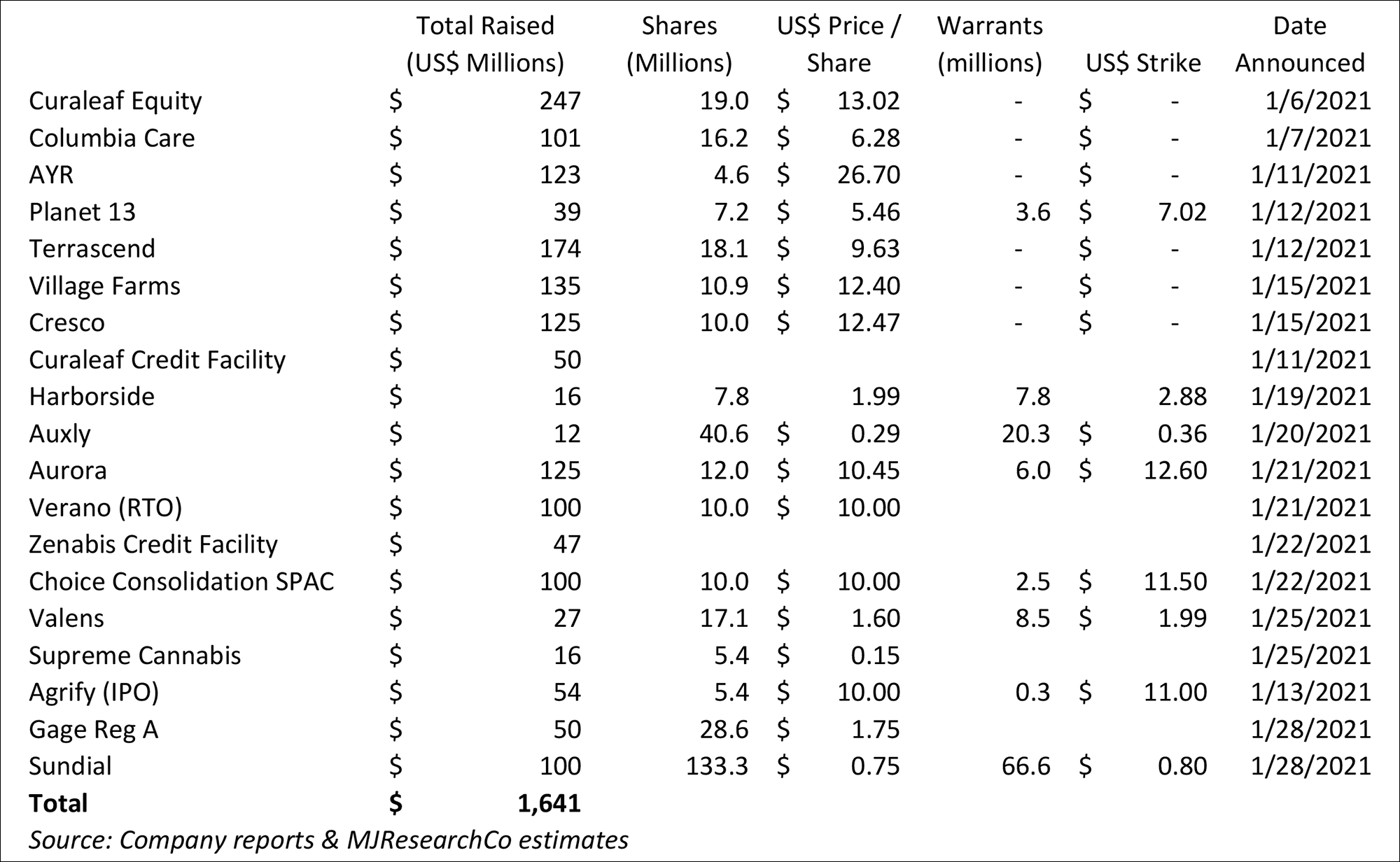

With that investor enthusiasm, 18 companies have announced or issued $1.6 billion in new capital.

While some of this capital will be allocated into high-return new projects, some will be invested in disappointing projects – or even wasted on poor decisions and bad business models.

The key to determining that is the incremental return on invested capital (ROIC).

If the ROIC is high, the capital is used to expand high-return projects to the benefit of shareholders and the industry. Smart investors are happy about this.

Some projects could generate lower returns than expected, such as when excessive capital raises led to excessive cultivation capacity in Canada.

Ultimately, total supply was 2.5 times demand, which led to declines in cannabis prices that pressured margins and eventually reduced the returns on capital until new managers began to reduce excess capacity.

Or the capital might simply be spent on low-return luxuries for self-interested management at shareholders’ expense.

Determining which company is doing what kind of investments requires understanding the fundamentals of the business, the strategy, the uses of the new capital and the incentives and past behavior of management.

Over time, the only true value will be created by businesses providing desired services to paying repeat customers at good margins – not hoping to sell a never-profitable, low-ROIC business to a greater fool.

Mike Regan is the founder of MJResearchCo.com and a regular contributor to Marijuana Business Daily. He and fellow analyst Colin Ferrian can be reached at mikeandcolin@mjresearchco.com.