(Editor’s note: This story is part of a recurring series of commentaries from professionals connected to the cannabis industry. Nick Richards, a partner in the tax practice group at Greenspoon Marder in Denver, advises cannabis stakeholders in tax and regulatory compliance matters. He has been a tax attorney for more than 20 years, beginning with the IRS. This story also is part of a special series revealing key elements of more than 200 pages of internal IRS documents obtained by MJBizDaily.)

I’m angry. There are too many examples of innocent people suffering because of our nation’s politics and prejudices.

The Internal Revenue Service’s audit program and enforcement of Section 280E of the federal tax code are another example.

In fact, Section 280E was born of politics – at the height of the war on drugs, in 1982.

Later, when California legalized medical marijuana in 1996, the war found a partner in the IRS.

The Clinton administration even issued a memo that same year pledging to use Section 280E to destroy legalized cannabis. And, as Marijuana Business Daily showed us this week, the ripple effects of that policy still reverberate today.

When I was an attorney for the IRS, I was involved in its fight to shutter abusive tax shelters and promoters.

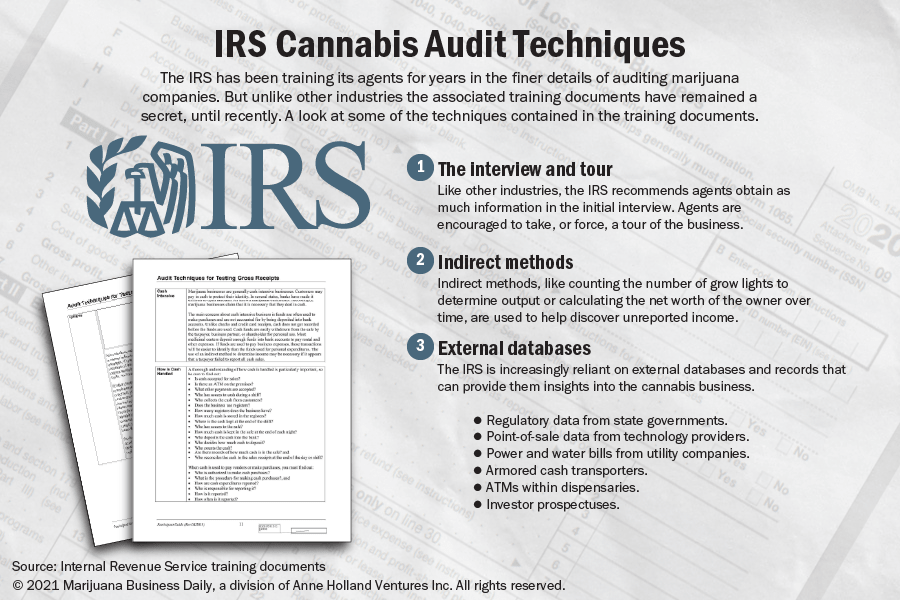

The IRS audit program documents that MJBizDaily obtained show that the agency is using the same tactics against the cannabis industry that we used against tax cheats – targeted audits, criminal investigations, Compliance Initiatives, senior revenue agents, coordinated collections.

The documents show the government’s huge, coordinated effort to penalize the industry and utilize its ability to disallow deductions to the fullest extent possible under federal law.

But one thing the documents – and IRS court victories – fail to show is the difficulty the IRS faces in collecting the “phantom” income tax.

‘Phantom income’

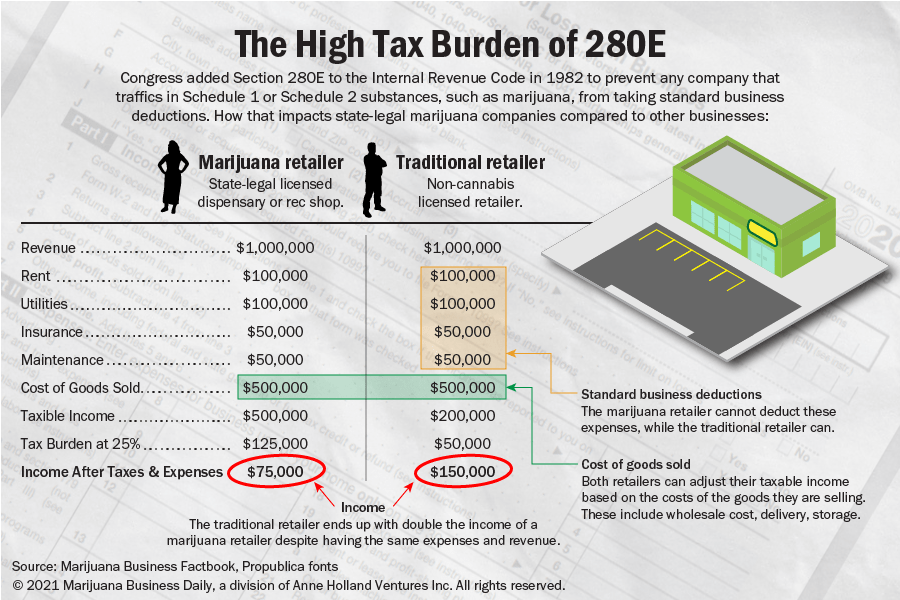

Section 280E creates “phantom income” – meaning the tax is levied on income that was never received. In the cannabis industry, that amount can be staggering.

But the truth is, the IRS can’t collect the tax from the business if it can’t pay it – because the IRS cannot seize and sell marijuana.

But it is more than that. Our income tax system is “pay as you go,” meaning when you receive money, you pay tax on it through paycheck withholding or quarterly tax payments.

Section 280E is different. There is no “income” with the assessment of the tax.

As a result, I have many cannabis company clients that owe millions under 280E. They might never be able to pay those tax bills. And they might not have to.

Our tax system, the rules and the IRS’ authority are all specifically geared under the 16th Amendment to determine “income” or “gain” on which tax is applied.

The determination is simple with a salary: Your paycheck is income, and tax is applied and withheld. But in a business, it is more complicated.

More in this series

- Confidential IRS marijuana guide details audit procedures for agents to follow

- Documents reveal how IRS became more adept at evaluating marijuana company taxes

- Newly released IRS documents detail efforts to collect taxes from marijuana companies under 280E

- A primer on marijuana-related IRS terminology

A business that sells a product is made up of different types of assets – goods for sale, equipment and the business itself.

The costs that a business incurs are accounted according to the life of the asset to which they relate.

Thus, the cost of equipment is deducted over the useful life of the equipment. The cost of acquiring or producing a product is deducted when the product is sold.

But there are also “ordinary and necessary” costs of running a business that are not directly related to the product costs or equipment.

These costs are called “ordinary and necessary” because they are the legitimate costs of building and operating a business itself.

As such, deductions for these costs should attach to the business itself and be taken against the income of selling the business.

But the tax code allows deductions for the “ordinary and necessary” business expenses against current income – rather than when the business is sold.

The difference is timing.

280E bars cannabis industry deductions

For cannabis companies, 280E bars deductions for “ordinary and necessary” business expenses.

But what happens to a disallowed deduction? Wouldn’t the ordinary and necessary expense just revert back to being attached to the business itself – to “basis” in the business?

Basis can be complicated, but essentially it is an owner’s contributions to a business that, when returned, are not taxed.

It’s kind of like the down payment on a home.

Our system taxes gain. If the disallowed “ordinary and necessary” expense is allowed as basis, then the requirement is satisfied. If not, then Section 280E is a violation of the 16th Amendment.

I have had a number of discussions with the IRS and tax professionals regarding this position, and it is hard for anyone to dismiss it out of hand – because an ordinary and necessary expense can’t just disappear. And it makes 280E and the 16th Amendment work.

That said, the tax code also includes rules that are problematic to the concept that a disallowed deduction should increase basis. In fact, some rules deem disallowed business expenses as personal and they actually reduce owner basis.

But those rules deal with expenses that are not ordinary and necessary and, I would say, are not required in the determination of gain.

280E fails to level playing field

When I was an IRS trial attorney, I took an oath, like all IRS employees, to treat all taxpayers equally and fairly under the law.

But there are numerous examples where 280E produces incongruent results.

For example, the U.S. Tax Court recently held that marijuana stores cannot capitalize the packaging expenses that the code requires of every other type of business – including marijuana growers and manufacturers.

Marijuana growers are hardly impacted by 280E at all, while medical dispensaries are severely penalized.

The same expense in the hands of a grower is deductible. But for a reseller, it is treated as taxable income.

For example, equipment for a grower is allowed – but not for a store.

And the simple act of forming a marijuana business as a C corporation or LLC determines who ultimately owes the phantom income tax.

If the company is a C corp, it owes the tax. But generally, if the company is an LLC or S corp, the phantom income tax is the owner’s personal liability and can be collected from the owner’s personal assets (home) and income.

Perhaps most disturbing is that 280E drives up the costs of legal, regulated marijuana, making room for the illegal market to compete and increasing the price of medicine for people who really need it.

The truth is, 280E turns our tax code upside down and does not meet the needs of society.

The IRS should make clear that an “ordinary and necessary” business expense that cannot be claimed as a deduction or cost of goods sold (COGS) under 280E is an increase to basis in the business.

Which brings us back to the reality that 280E is really about timing. The government has the authority to determine the timing of a business expense, but it cannot take it away forever.

If this approach were adopted, it would mean that 280E is not unconstitutional because gain under the U.S. Constitution would be determined on the ultimate disposition (sale or failure) of the business.

Good news for the cannabis industry – perhaps better than legalizing marijuana if legalization replaces Section 280E with an excise tax.

Moreover, this resolution would not reduce the effectiveness of 280E on illegal drug dealers, who would unlikely be able to sell their businesses, even if they are incorporated.

It also would resolve collection issues for the IRS, as the agency could wait until a business was sold or failed to “true up” the 280E deductions to accurately reflect any gain.

Small-business exception

Finally, there has been a lot of talk about the small-business exception to the inventory accounting rules – Section 471(c) of the federal tax code.

The small-business exception is, again, just timing. Except Congress took away the IRS’ power over timing and specifically provided that all small-business taxpayers have the authority to determine the timing of deductions.

And, perhaps predictably, the IRS recently included a statement in its regulations that could remove the benefits for the marijuana industry.

This is another example of the politics the industry faces, because the IRS statement directly contradicts the statute, the intent of Congress and its authority under the 16th Amendment.

I work with the IRS every day, and I know many of the agents understand these problems and wish the IRS would do something about them.

Unfortunately, there are others who seem to enjoy the problems and flexing their 280E muscles.

The IRS should remember its oath, put its politics aside, stop targeting the marijuana industry and stop bending the 16th Amendment in its war on drugs.

The war is over – the industry is here to stay. Prohibition lost.

Nick Richards is a partner in the tax practice group at Greenspoon Marder in Denver. He can be reached at nick.richards@gmlaw.com.

The previous installment of this series is available here, and MJBizDaily‘s special series on the IRS is available here.

To be considered for publication as a guest columnist, please submit your request here by filling out our form.