Large marijuana multistate operators are enjoying lower loan interest rates these days, thanks to stronger balance sheets and the industry’s increasing stability as more states legalize MJ and federal reform appears inevitable – although progress in Washington DC remains slow.

The lower rates have boosted the investment muscle of these MSOs as they expand their presence in fast-growing state markets.

At the same time, the lower debt costs highlight the interest-rate gap between large operators and smaller businesses, including minority-owned companies.

Investors, in general, perceive smaller companies to be riskier, lenders aren’t as interested in doing smaller loans, and entrepreneurs are hesitant to put up the personal collateral that might be required to secure the loans.

“Small businesses are not enjoying the (same) benefits,” said Amber Littlejohn, executive director of the Washington DC-based Minority Cannabis Business Association.

Rather, Littlejohn noted, the vast majority of minority businesses at a similar stage in their development “either get stalled because they don’t have the money to go further,” sell out entirely, self-fund or give up equity in exchange for capital from private investors.

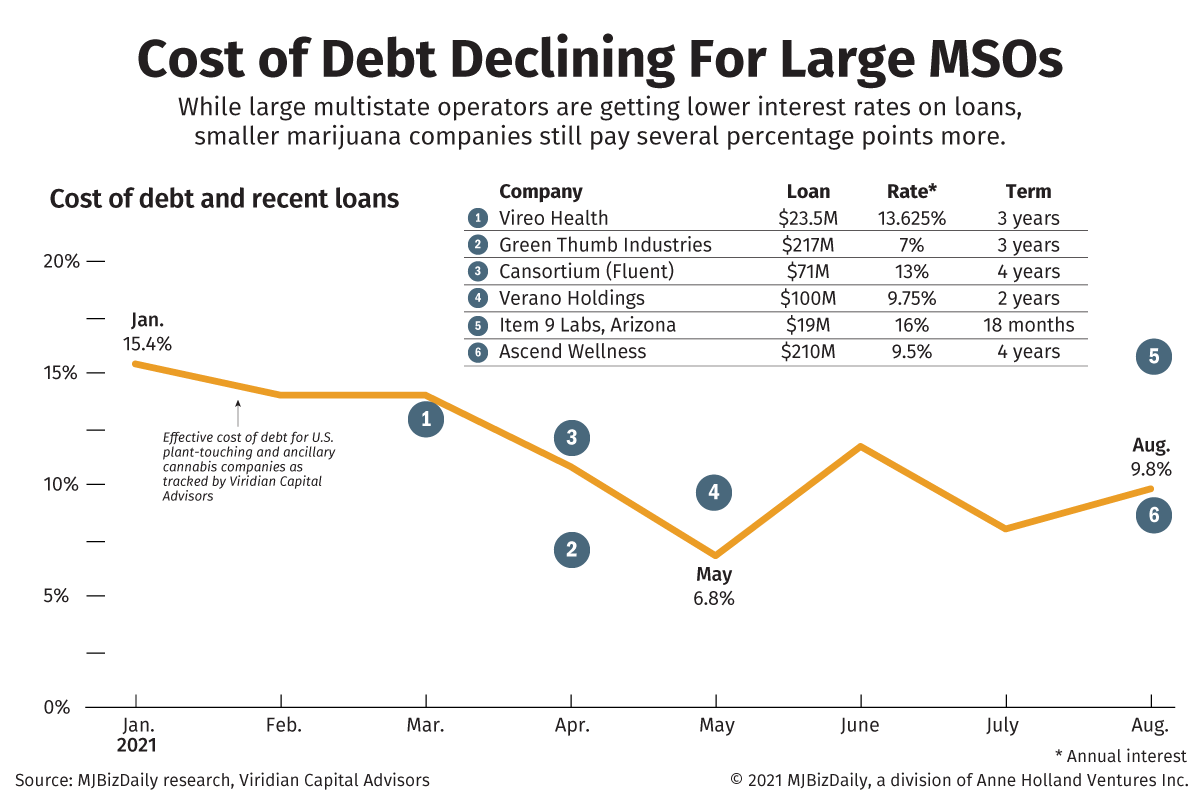

Large MSOs recently have been raising capital and paying annual interest rates of about 9%-10% – several percentage points below rates a year ago.

Illinois-based Green Thumb Industries nabbed one of the sweetest deals in April – a 7% interest rate on a three-year, $217 million loan.

“History has taught us that the winners in new industries are those with the lowest cost of capital and the strongest balance sheets,” GTI founder and CEO Ben Kovler said in a news release announcing the deal.

Soon after, Green Thumb announced a deal to acquire one of Virginia’s five medical marijuana licenses.

“We see interest rates are going down for better-positioned operators,” said Matt Karnes, founder of New York-based GreenWave Advisors, a marijuana financial research and consulting firm.

Karnes attributed the trend to the combination of “impressive operating metrics” and the perceived risk declining “as we get closer to the end of federal prohibition.”

Granted, the marijuana industry is still paying far higher interest rates versus mainstream corporations in other industries. The average cost of corporate debt has hovered around 3%, according to data compiled in early 2021 by New York University’s Stern School of Business.

But the impact of the lower rates can be significant for large MSO.

A lower interest rate of just 1 percentage point on a $200 million loan translates into interest savings of $2 million a year. A 3-percentage-point difference on a $200 million loan generates interest savings of $18 million over three years.

Smaller MSOs, however, aren’t enjoying the same favorable rates as their larger counterparts. These companies typically receive annual interest rates of about 13%, according to an MJBizDaily examination of recent debt deals.

As is the case in residential real estate, construction financing loans can be even more expensive.

Phoenix-based Item 9 Labs, for example, is paying a 16% annual interest rate for a construction financing loan to expand its cultivation and processing facility in Arizona and complete a project in Nevada.

Uneven benefits

New York-based Viridian Capital Advisors, which monitors capital raises, recently noted the declining cost of debt since the beginning of the year, although the trend line is choppy on a month-by-month basis. (See chart.)

Viridian’s data is based on company-provided transaction terms, which is readily available from public companies. But private companies often don’t provide such data.

The chart accompanying this story shows the effective cost of debt, which takes into account additional transaction terms such as investor discounts or warrants that entitle investors to buy stock at a specified price and time.

The value of debt raises through Sept. 10 are up nearly 80% versus the same period in 2019, according to a recent report from Viridian. Those raises account for the lion’s share of the total capital mix.

Frank Colombo, Viridian’s director of data analytics, wrote in an email to MJBizDaily that debt has become an increasingly cost-effective part of a cannabis company’s capital structure, given the lower interest rates and currently soft stock prices.

For example, if executives at a publicly held marijuana company thinks its stock price will rise due to progress in federal marijuana reform or some other factor, “it behooves you to issue debt now instead of equity, because you will be able to issue the equity later at a higher price and use the proceeds to take out the debt,” Colombo said.

Of course, lenders realize that too, Colombo said, so they often want to institute high pre-payment penalties if a company pays off the debt early so that it can capitalize on the higher stock price.

Theoretically, ancillary companies should be able to get even lower rates from traditional banking sources, given that they don’t touch the plant.

“But there are cross currents involved,” Colombo noted.

Ancillary companies typically are smaller and thus pay higher rates.

Meanwhile, the cost-of-capital landscape hasn’t changed much for small and minority-owned marijuana businesses.

The same barriers have existed since the start of the legal marijuana industry, Littlejohn said.

Many minority marijuana entrepreneurs, she said, rely on personal savings, credit cards, cash from second mortgages and money from family and friends to get started, and then self-fund or are backed by investors in exchange for equity.

Small businesses don’t have the collateral to put up to secure the loan like larger companies can, which leads to higher interest rates, Littlejohn said.

Mindset change needed

“One of the keys really is going to be that we have to reassess how we are looking at risk for small and minority businesses,” Littlejohn said.

That requires financial institutions and private-equity firms to change their mindsets and will test whether they are truly committed to equity in the marijuana industry as many say they are, she said.

Littlejohn also noted the unintended consequences of well-intentioned social equity programs.

Massachusetts regulators, for example, set aside delivery permits for social equity and economic empowerment applicants for a three-year period.

That includes a courier-type service to make deliveries for licensed retailers for a fee, as well as license that enables a company to purchase products from cultivators and processors, warehouse the goods and deliver them directly to customers.

Judging by the number of applicants, there’s plenty of interest in the program.

But “funding has been a nightmare” for those interested in the warehouse model, Littlejohn said.

MSOs are looking toward the day when they can do the delivery themselves, she added, so they aren’t so interested in supporting the delivery services. And funders want to get behind the MSOs, not equity applicants.

“So it makes it really challenging to get a business up and running,” Littlejohn said.

Steve Hawkins, executive director of Marijuana Policy Project, said in a recent interview that he’s encouraged by some of the new social equity initiatives.

He noted, for example, the announcement earlier this year that New York fund manager JW Asset Management was teaming up with former NBA All-Star Chris Webber to launch what is hoped to be a $100 million private equity fund to invest in underrepresented marijuana entrepreneurs.

But other than those kinds of efforts, “finding the operating capital in this environment is still difficult,” Hawkins said.

“If history is any guide, it’s going to continue to be a problem.”

Jeff Smith can be reached at jeff.smith@mjbizdaily.com.