(The chart above has been updated to include 20 government-operated cannabis stores in British Columbia.)

Quebec has fallen far behind its nine provincial counterparts in terms of regulated cannabis stores per capita, limiting consumer access to brick-and-mortar stores in Canada’s second-biggest recreational marijuana market.

The province is Canada’s largest by area and second-largest by population, with roughly 8.5 million people, or nearly a quarter of the country’s total population.

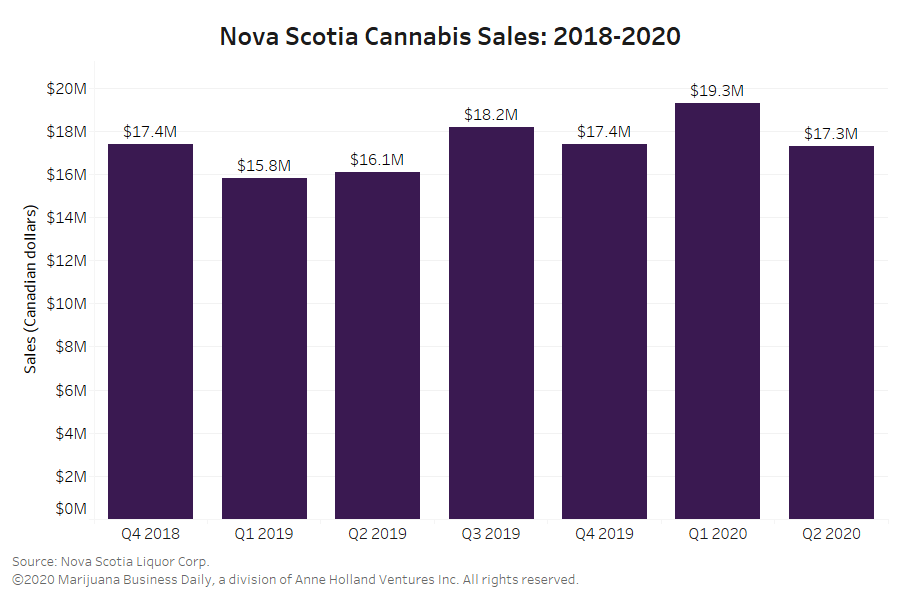

Physical store openings appear to be driving growth in Canada’s regulated cannabis market, with ever-growing monthly retail sales figures correlating with increasing store counts.

But Quebec’s government-owned Société québécoise du cannabis (SQDC) cannabis retailer, which has a total monopoly on regulated recreational cannabis sales in the province, has opened fewer than 50 stores since legalization in late 2018.

That stands in stark contrast to provinces where new private-sector retailers are opening every week.

Alberta continues to lead the pack in cannabis store rollouts among Canadian provinces, with more than 500 store licenses serving a population roughly half of Quebec’s – about 11.5 licenses issued per 100,000 people.

Quebec’s per capita store count comes in dead last among the 10 provinces, with roughly 0.5 stores per 100,000 Quebecois.

100 stores planned by 2023

The SQDC has 45 locations open across Quebec as of this week, when it opened two new stores.

The retailer told Marijuana Business Daily that it aims to open 70 locations by the end of March 2021 and 100 by March 2023.

Earlier this year, Quebec media reported that the SQDC planned up to 150 stores by 2023.

However, SQDC spokesman Fabrice Giguère said the report was inaccurate, based on an erroneous interpretation of a public tender.

“There were never plans to go to 150 stores,” he said.

But even with 100 stores by 2023, Quebec’s per capita store count would lag.

The 100-store target “doesn’t sound very ambitious to me,” said Michael Armstrong, a Brock University business professor who analyzes Canada’s legal cannabis market.

“That sounds like a good target for, by the end of next year,” he said.

Armstrong estimates Quebec’s population could support roughly 600 cannabis stores.

Strategic store placement

SQDC spokesman Fabrice Giguère told MJBizDaily that the retailer prioritizes carefully chosen store locations over sheer numbers.

He argues that retail sales figures prove the approach is working.

“For the month of June, our revenues were CA$40 million ($30.4 million at current exchange rates),” Giguère said.

By comparison, he observed, regulated sales in British Columbia – which has far more retail outlets than Quebec, albeit a smaller population – were CA$29 million that month.

Giguère said that, since adult-use legalization in October 2018, “Quebec has always, always been consistently in the top three provinces, sales-wise, and we have always had a very low number of stores.”

The SQDC’s business plan involves placing stores in strategic locations across the enormous province, Giguère explained.

“You can have a low number of stores that are strategically positioned and yet be a great success and have a lot of sales and make sure that they can service the population correctly.”

Giguère said SQDC stores are located in all but two of Quebec’s 17 administrative regions.

Online ordering is available to customers in more remote areas.

However, online transactions were only 8.2% of the SQDC’s total sales in the fiscal year ended March 28, a figure that underlies the importance of brick-and-mortar locations in capturing market share away from illicit operators.

At the end of that fiscal year, the retailer estimated it had captured 30% market share away from the illicit market.

“At first we thought that the web would be a driving growth force,” Giguère said.

“But then we (came to) realize that stores really are the backbone of our growth.”

The SQDC’s limited store count might have played a role in holding back at least one major Canadian cannabis producer with a critical interest in Quebec.

Hexo Corp., which has a five-year supply contract with the SQDC, said in a regulatory filing that sales through the retailer failed to meet an expectation of 20,000 kilograms in the first year of legalization.

In light of market conditions, including “fewer brick and mortar SQDC stores than originally scheduled for initial rollout,” wrote Hexo management, “we no longer expect to achieve the previously anticipated (35,000 kilograms) in the second year of legalization under our contract with the SQDC” or a 45,000-kilogram target for the third year.

Strengths as a monopoly

In spite of the SQDC’s lack of stores, business professor and cannabis market analyst Michael Armstrong said the retail monopoly’s business model has succeeded in other areas.

“They seem to have a definite strategy: low price, compete with the black market,” he said.

“They haven’t opened enough stores to reach the whole market, that’s the biggest downside. But the upside of that is, it meant they’ve had a very efficient operation so they can charge low prices and still cover their costs.”

Armstrong points out that the SQDC turned a profit in its second fiscal year ended this March, returning CA$26.3 million to provincial coffers.

SQDC spokesman Giguère wouldn’t disclose the retailer’s margin but said it keeps prices low in part by using a direct-to-store supply chain and running a lean head office with fewer than 30 employees.

The SQDC sees pricing as a tool “to migrate people from the black market to the legal market,” Giguère said.

“So we want to have a price that will be on par with that reality.

“We also want to remain profitable,” he continued.

“But also, we don’t want to lower the price to the point where cannabis would (be) perceived as a mundane product, because it’s not.”

Michel Timperio, chair of the board of the Quebec Cannabis Industry Association and president of Neptune Wellness Solutions’ cannabis business, commended the SQDC’s aggressive pricing strategy and market penetration.

“People were kind of reluctant to see government involvement in a store. … But after the experience, one has to admit that they’re doing pretty goddamn good,” he said.

No politics in store counts

Armstrong, the business professor, suggested one plausible reason the government-owned retailer might not have opened more stores more quickly: the politics of the province’s current leadership, a majority government under the right-wing party Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ).

“That’s speculation on my part, but it’s very obvious that the public policy of the provincial government and the business policy of the cannabis agency are not a nice match,” Armstrong said.

Since taking power just before Canada legalized cannabis in October 2018, the CAQ government has enacted a number of policies that hinder the industry.

Those policies include:

- Increasing the age for cannabis use to 21.

- Banning the sale of cannabis vape pens and many types of edibles.

- Expanding a ban on opening SQDC stores within 250 meters of a school to apply to post-secondary institutions in addition to primary schools.

However, SQDC spokesman Giguère said the retailer’s store numbers and deployments are free from political interference.

“We do our own projections, and we choose how and where we want to put our stores,” he said.

Giguère acknowledged that more physical cannabis stores boost regulated market growth in Quebec.

But, at the end of the day, the government-owned retailer is motivated by something other than pure profit.

“(We) want to make sure that we will have a number of stores strategically positioned that will help us to fulfill our mandate – that is a health-protection mandate – by migrating people from the black market to the legal market,” Giguère said.

“And so that’s really our goal.”

Solomon Israel can be reached at solomon.israel@mjbizdaily.com