(This is Part One of a special series revealing key elements of more than 200 pages of internal IRS documents obtained by Marijuana Business Daily related to the enforcement of Section 280E of the federal tax code and the cannabis industry. The introduction is available here. The documents can be accessed here.)

(This is Part One of a special series revealing key elements of more than 200 pages of internal IRS documents obtained by Marijuana Business Daily related to the enforcement of Section 280E of the federal tax code and the cannabis industry. The introduction is available here. The documents can be accessed here.)

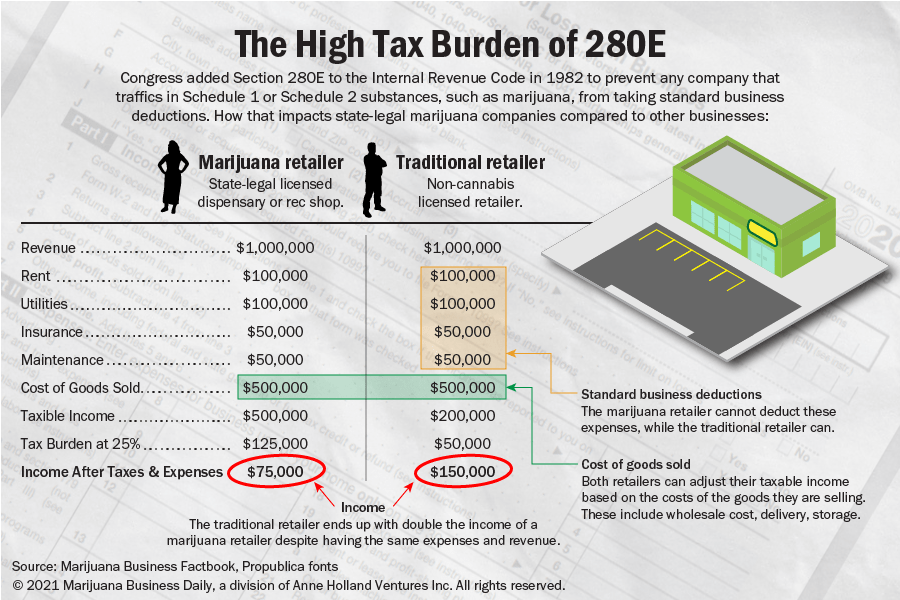

The Internal Revenue Service has been scrutinizing the books and records of marijuana companies for more than a decade, ordering business owners to hand over tens of millions of dollars in unpaid taxes.

That fact isn’t necessarily news to many industry insiders, but what has largely been kept under wraps is the agency’s decision to undertake at least five sweeping, multiyear audit programs that targeted scores of cannabis businesses in at least four states across the West and in Detroit.

The audits – known as Compliance Initiative Projects” (CIPs) – were run by at least three different IRS field offices.

Their goal: to enforce federal tax code compliance, based on the agency’s belief that many marijuana companies were skirting Section 280E of the federal tax code and claiming illegal write-offs.

The IRS confirmed to Marijuana Business Daily that audits connected to at least two of the CIPs are still ongoing in Detroit and the “Western Area,” which includes Colorado.

Although several of the CIPs were disclosed in a report last year issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, documents detailing four of the five audits have been released for the first time through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request filed by MJBizDaily.

They show the IRS found it was a more productive use of agents’ time and resources to audit marijuana businesses than other mainstream industries after the agency calculated that marijuana companies owed more in unpaid taxes than their federally legal counterparts.

The documents also detail how the IRS improved its cannabis audit results over the years based on information gleaned from those investigations.

In short, the IRS was able to collect as much in federal taxes as possible under the law from state-legal marijuana businesses – anywhere from two to four times as much in unpaid taxes, or revenue – as the agency did from mainstream companies also identified as ripe targets for audits in a given fiscal year.

That has likely cost the cannabis industry untold millions of dollars.

More in this series

- 280E is a political weapon targeting marijuana companies, but there may be a fix

- Confidential IRS marijuana guide details audit procedures for agents to follow

- Newly released IRS documents detail efforts to collect taxes from marijuana companies under 280E

- A primer on marijuana-related IRS terminology

One of the audit projects – focused on Colorado cannabis businesses from January 2016 to June 2017 – unearthed more than $43 million in unpaid federal taxes, according to the documents.

It’s unclear the amount in unpaid taxes the IRS has assessed – or collected – in total from its audit projects or the marijuana industry in general.

Asked how much in the way of taxes the IRS has collected from the marijuana industry in each of the three most recent tax years, agency spokeswoman Sarah Maxwell responded in an email to MJBizDaily, “This information is not currently available.”

But the documents suggest the amount has been considerably more, on average, than the IRS has collected from mainstream companies.

“They were pulling in no less than two times their average hourly revenue from audits,” California tax attorney Katherine Allen of Wykowski Law said after reviewing the CIP documents.

“It quantifies their financial incentives and their interest in the industry.”

Allen noted the CIP findings make sense in the larger context of other signs pointing toward a growing number of marijuana industry audits.

“This is kind of consistent with how we’re expecting more and more audits of the industry going forward,” Allen added.

“They pulled millions of dollars a year just from those CIP’s, which is proof of concept within the IRS as to why they would target the industry.”

Maxwell denied in an email that the IRS prioritizes audits of marijuana companies over traditional businesses, adding that the agency’s “approach is the same as (with) mainstream industries.”

“We audit taxpayers with a high risk of non-compliance from any industry,” Maxwell wrote. “Our mission is to promote voluntary compliance, including compliance with IRC Section 280E.

“Promoting voluntary compliance is accomplished through enforcement actions (i.e., audits), outreach and education.”

The IRS has performed at least five such targeted audits focused on the cannabis industry since 2010, and the agency’s financial results have clearly improved with time.

According to the documents, an early round of California audits generated an average of $945 per hour in unpaid taxes from cannabis businesses for the agency in 2012 versus $544 an hour from mainstream industries at the time.

By 2019, the average in unpaid taxes had leaped to $2,752 from marijuana industry audits in Colorado versus $1,065 an hour from mainstream businesses, according to a report by a Treasury Department inspector general unit.

The first batch of audits focused mainly on California, followed by Colorado – with some businesses in Arizona and New Mexico wrapped in during a project extension – according to the documents.

The IRS did not disclose any documents related to the fifth CIP, which was authorized for Detroit at the end of 2017.

Although the IRS heavily redacted the documents, they still reveal enough detail to show the agency’s longstanding interest in the marijuana industry is easily justified from a financial point of view.

The documents repeatedly stress the agency is better served by auditing marijuana companies than any other industry.

Denver-based tax attorney Nick Richards agreed with Allen’s assessments of the CIPs, noting the report from the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) last year also urged more marijuana company audits.

“Definitely, you see in these CIP’s, they’re glowing. ‘We get more money than anything, let’s do more,’” Richards said. “Then we see TIGTA is saying the same thing in their review. ‘Do more, do them better.’

“So you have to assume we’re going to start to see increased audits.”

It began in California

According to one excerpt from the 2010 authorization form for the first CIP in California:

“The objective is compliance. … There is a high likelihood that a good deal of the 400+ ‘Medical Marijuana’ stores are non-filers and/or are not reporting there (sic) sales.”

“If successful, this project could go nationwide and help find a good number of under reporters and non-filers were (sic) cannabis has been legalized by the state.”

By June 2012, IRS agents had closed 91 cases from the first CIP.

And they found the audits to be a financial windfall: The agency, in effect, took in almost $950 per hour of IRS agent work digging up unpaid taxes versus nearly $545 an hour for mainstream businesses that also were likely to be targeted for audits.

Though that’s less than double the revenues the IRS generates from mainstream businesses, the margins would quickly improve as the years progressed.

In justifying an audit project extension, an IRS agent reported the cannabis industry exams took, on average, about a third less time to comb through marijuana company returns than the returns of mainstream businesses.

In particular, only 3% of the cannabis returns had no errors or adjustments compared with 21% in other industry audits, which are identified in the documents as “DIF results.”

In other words, the findings demonstrated that almost 97% of cannabis companies examined had underreported their federal tax liabilities and thus owed the IRS more money.

Richards, the Denver attorney and former IRS lawyer, said “DIF” is IRS jargon for a computer program that helps identify tax returns that are likely to yield unpaid taxes through audits.

The acronym is short for “Discriminant Function” system.

“It’s like their secret sauce. It’s how they find audits, through a DIF score,” Richards said. “That DIF score is their general population audit finder that the computer just uses across the board.”

The DIF averages are already considered an important niche within the totality of business tax returns filed each year with the IRS.

The program identifies companies that are likely to have underpaid on federal taxes. Companies with higher DIF scores are thus more likely to be hit with audits, Richards said.

What the CIP documents show is cannabis companies provide even better financial results than mainstream businesses that the IRS believes aren’t paying all their taxes.

“The important point is these aren’t just mainstream businesses; these are specifically selected mainstream businesses that the IRS believes would make for good audits,” Richards said. “We’re comparing two targeted searches here.”

Which drives home the point that, to the IRS, the cannabis industry is the cream of the crop when it comes to audits and unpaid taxes.

As IRS gets more adept, more taxes identified

The original California CIP was so successful that, in July 2012, it was extended to a “Part Two,” essentially a second audit project, according to the documents.

At the end of 2013, the second portion of the CIP was extended yet again, with a request to add marijuana companies in Arizona and New Mexico, which both had operational medical marijuana markets.

IRS tax assessments kept rising as agents continued finding cannabis companies that were either deliberately filing inaccurate tax returns or filing erroneous ones that didn’t pay what the agency contended the businesses owed under 280E.

According to the IRS documents, the audit projects closed 173 cases by November 2013.

By that point, the effort had resulted in $1,375 per hour in unpaid taxes, or added revenue, for the IRS compared with $493 per hour for the average mainstream case – a significant widening of the financial benefits for IRS agents over the 2012 results.

Audits of marijuana businesses also:

- Took less time.

- Produced a higher rate of changes to federal tax returns, which resulted in the IRS assessing additional taxes.

- Led to more tangential exams and audits (identified in records as the “pick-up rate,” according to Richards).

“Every metric above is significantly better” in marijuana industry audit results than in other industries, according to an agent’s request for an 18-month extension to the second part of the California CIP.

“What they’re saying is, ‘Look at how much better these marijuana audits are than our general program DIF score audits. Our best secret sauce computer algorithm merely produces $493 an hour. But, boy, if we just audit cannabis companies, we’ll get $1,375 per hour,’” Richards said. “It really justifies (the audits).”

The two-part California audit concluded in 2015 after more than five years, and the IRS tax assessments from marijuana audits ballooned during that period.

According to the termination report, “Examinations resulted in $2,788 per hour, which is better than the SBSE (redacted) DIF average of $686 per hour.” (SBSE is an acronym for Small Business Self Employed, a division within the IRS.)

The termination report noted that the project was “valuable education regarding non-deductible medical marijuana expenses.”

The Colorado projects

The first Colorado CIP began in 2011, a little more than a year after the California audit project launched.

According to the IRS document authorizing the Colorado probe, the audits had similar aims: to “determine compliance of reporting under section 280E.”

The document also described the medical cannabis industry at the time as “estimated to be worth $10 to $120 billion, the largest cash crop in the country.”

The Colorado audit was intended to be limited to “50 taxpayer contacts,” but the termination report filed in 2014 revealed that the project looked at 102 returns, according to an analysis by Richards.

The effort also resulted in seven taxpayer returns being referred to the IRS’ criminal investigation unit.

The audit project reinforced the IRS’ earlier findings: The marijuana industry yielded more money for less time.

“With the exception of cycle time, the results are all better than DIF results,” the termination report noted, though it didn’t list specific DIF results.

For example, the average unpaid tax bill, or tax deficiency, was $15,781 for 67 cannabis returns – in other words, that amount refers to the difference between what a taxpayer reports on their return and what the IRS has determined is owed.

For another nine marijuana returns, the average deficiency was $1,814.

For 26 other marijuana returns, by comparison, the average deficiency was zero, though three of those were referred for criminal investigation.

The audit project’s total average dollars per hour in unpaid taxes was $1,211 for marijuana companies, with a no-change rate of only 6% for most of the returns.

In other words, 94% of cannabis returns in the first Colorado audit were found to have unpaid taxes.

The IRS began a second CIP in Colorado in January 2016, two years after recreational marijuana sales began in the state.

“Even though Colorado law mandates strict regulations and licensing of this industry, preliminary research shows a high number of federal non-filers,” the authorization report notes.

“Another compliance concern is the accurate reporting of gross income. Because the industry is so cash intensive, the likelihood of an understatement is high.”

The authorization report anticipated only 30 taxpayer contacts. And, by this point, the IRS had the Colorado Department of Revenue to help identify businesses to target.

The Colorado agency posted information about all licensed marijuana businesses online, a practice that has since become common among state governments that issue cannabis business licenses.

“The (CIP audit) process begins with downloading the list of licensees from Colorado Department of Revenue,” the authorization report notes.

According to the termination report, the project came to an end in June 2017 after IRS agents examined 170 federal tax returns.

The results:

- For 103 returns, the average tax deficiency was $120,301.

- For 29 returns, the average deficiency was $331,902.

- For 35 returns, the average deficiency was $576,323.

- For three returns, the average deficiency was recorded as more than $21 million. However, the IRS clarified in follow-up emails to MJBizDaily that total was incorrect and the actual average deficiency for those returns was $282,596.

That’s a total of more than $43 million in unpaid taxes from one audit project.

The agents handling the final Colorado audits reported a “wide variety of expenses” that were deducted improperly, along with unreported expenses that were subject to 280E.

The termination report also suggested an “expansion of CIP into national CIP.” If the IRS were to act upon such a recommendation – which isn’t unlikely, according to Richards and other sources – that could mean a surge of 280E audits of MJ businesses across the country.

The only reason the Colorado audit project wasn’t extended to “Part Two” like the California CIP was “resource constraints,” according to last year’s Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) report.

There’s also at least one other CIP that is specific to the city of Detroit, which was authorized on Dec. 31, 2017, according to the TIGTA report.

Asked whether the IRS has taken the suggestion of its agents to pursue a national CIP, the IRS’ Maxwell responded in an email that the agency “recognizes the marijuana industry is growing and is assessing potential areas of noncompliance to develop the appropriate compliance actions as well as additional outreach and education needed to improve voluntary compliance.”

Colorado, Detroit CIPs remain active

Despite the IRS’ 2017 termination report regarding the Colorado audit project, many individual audits connected to that CIP and the Detroit CIP remain active today, Maxwell confirmed in early April.

According to the TIGTA report, in the “Western Area” alone, IRS agents were still examining CIP-related marijuana business tax returns, well after the Colorado audit project was supposedly terminated.

“The 50 marijuana business examinations of the terminated Western Area Part 1 CIP are still in progress with closures being reported in FYs 2018 and 2019,” the report stated.

“Termination reports are filed based on the expected project completion date,” Maxwell wrote to MJBizDaily, not when all related audits are actually finished.

“There are examinations still ongoing for two of the CIPs mentioned in the report – the Detroit and Western Area,” she wrote.

Maxwell added that audits “often extend past the CIP completion date,” and the length of each audit is determined on a case-by-case basis.

Exams in the Colorado audit project for 2018 – a year after the CIP termination report was filed – resulted in an average of $2,497 per hour in unpaid taxes for the federal government, according to the report.

Surprisingly, marijuana business audits that weren’t part of the CIP resulted in an average of $3,375 per hour in unpaid taxes, an even better return than companies targeted for the project.

By contrast, mainstream business audits (identified in the report as “DIF returns”) resulted in only $967 per hour for the IRS.

The following fiscal year, the IRS’ results got even better, according to the TIGTA report.

For 2019 tax returns, the IRS found that marijuana returns in the “Western Area” audit resulted in an average of $2,752 per hour in unpaid taxes.

And marijuana business returns in the “Western Area” that fell outside the scope of the audit project still effectively generated $3,598 per hour in unpaid taxes, while mainstream business returns resulted in an average of $1,065.

Richards said he believes the CIPs might have been simply a starting point, and, once IRS agents had authorization to target the marijuana industry, they ran with it and kept the CIPs functionally alive.

Has your cannabis company been audited by the IRS? If so, we’d like to hear about it. Contact John Schroyer at john.schroyer@mjbizdaily.com.

(This series would not have been possible without support from several Marijuana Business Daily staff members, including Roger Fillion, Andrew Long and Jenel Stelton-Holtmeier.)