(This is the first of two stories focusing on small marijuana farmers in California’s Emerald Triangle. The second story is available here.)

California marijuana is world-renowned. But since the state’s legal market launched in 2018, the small Emerald Triangle farmers arguably most responsible for that reputation are largely getting left out when it comes to credit for the quality of the state’s marijuana crop.

Unlike California’s famed winemakers, these craft growers face systemic hurdles because they usually can’t afford the tens of thousands of dollars – or, in some cases, hundreds of thousands – it would cost to set up and manage their own branded products.

The current market, in effect, is disenfranchising small farmers by winnowing the pool of brands to include only well-financed growers and those who have the right industry connections.

That has left many craft growers without a straightforward path to sell their carefully bred strains directly to consumers – at least for now, though there is hope the situation will change thanks to a new appellation program and cooperatives.

The current hurdles were established – and continue to evolve – by regulations that were first written in 2015 by state lawmakers, which have hampered craft growers since they were implemented in 2018, when the adult-use market launched.

One of those rules stipulates that growers must use a middleman – distributors – to get their products to market, or perhaps sell as much as possible at a licensed event such as the Emerald Cup.

“We got really kind of screwed with the inability to sell direct to consumers,” lamented Robert Steffano, who owns Villa Paradiso, a small farm in Humboldt County, which comprises the Emerald Triangle along with Mendocino and Trinity counties.

“If we were able to reach out, like wineries can do, with their own mailing lists and clubs, you can start to build a following,” he added. “If we were able to do that, I’d be going gangbusters, because people who smoke my weed love it, and they want more.”

To create and maintain brands, small growers must navigate a labyrinthine set of regulations.

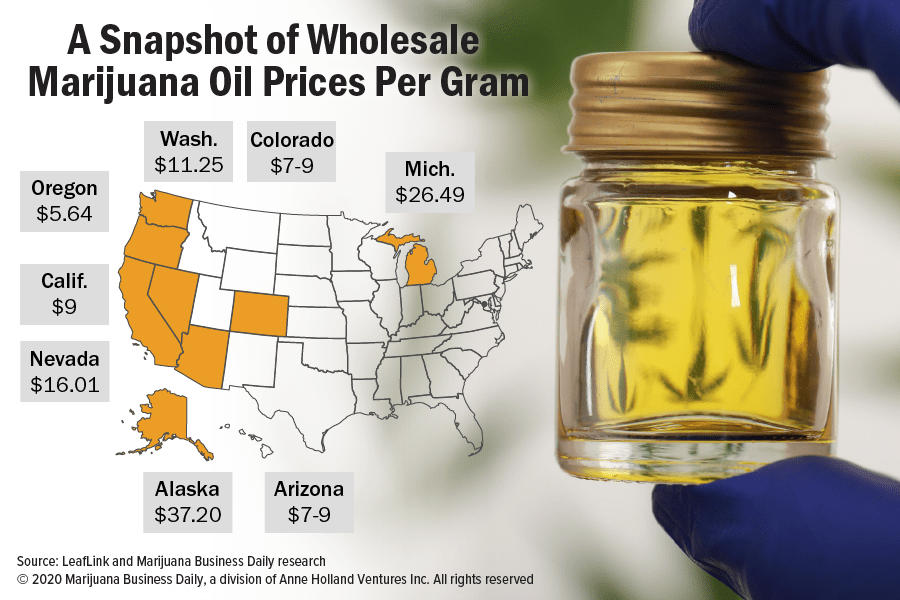

And the hurdles are typically so high that most resign themselves to anonymously supplying other companies with raw cannabis material through the wholesale market – instead of showcasing what could be the greatest diversity of marijuana strains in the world.

Many aren’t happy about it because they can’t get any acclaim for the quality product they’re producing and because it will make it that much more difficult to build more profitable companies in the long term.

In short, others get to claim bragging rights.

Distributors usually slap their own company names, logos and strain names on packages of flower, or they just resell the flower to other distributors, extractors or edibles makers who need raw material to make their own cannabis products.

“That’s really the hinge point, that we have to go through distribution,” Steffano said.

The landscape

Natalynne Delapp, the executive director of the Humboldt County Growers Alliance, estimated that of the roughly 750 licensed farms in the county, about 20% had brands that could be accurately labeled as “estate grown.”

That’s far below what she knows many of the craft growers would prefer, Delapp said.

But the amount of time, energy and money that it takes to establish a brand – and to maintain relationships with distributors and retailers – is prohibitive for most of the small farms in the Emerald Triangle.

What often happens, Delapp said, is that small farm crops get “pushed through bulk sales, mostly through the local distributors, who then sell it to secondary distributors, who then sell it out to white-label manufacturers.”

Scott Watkins, a consultant in Trinity County who runs Buildaberg, estimated around 10% of small farmers have their own brand and agreed that starting one from scratch can be daunting and expensive.

“You’re looking at a minimum of $50,000 just for the basics” of starting a brand line in California, Watkins estimated.

“More than likely, you’re looking at a team of people or two different companies that have a strategic alliance.”

In addition, Watkins said, small farms usually have the capacity to grow only about 1,000 pounds of cannabis a year, but distributors and retailers often prefer far more volume so they can keep shelves stocked year-round.

That’s an inherent problem for seasonal growers that harvest only once a year – as many do in the Emerald Triangle – versus indoor or greenhouse growers that have multiple harvests each year.

“In order to have a legitimate brand, you’re going to need that supply in order to match the demand across a large market like L.A. or in specific retail spots across the state,” Watkins said.

Barriers galore

Wendy Kornberg, the CEO and founder of Sunnabis, another Humboldt farm, said her family business had branded products on store shelves all over Northern California from 2015 until 2018, when the new legal market launched and brought with it new regulations.

That transition killed her ability to run her own brand, mostly because of the time and cost of dealing with the new rules.

That, in turn, meant her company had to retreat and pivot, and now she’s hoping that Sunnabis will make a return to store shelves in 2021 through a co-branding agreement with a distributor.

“We had to quit branding and move to just bulk sales,” Kornberg said. “We’re not legally allowed to package our own product because we don’t have a commercial building.”

Constructing a building that would be compliant with state regulations would cost her about $250,000, she estimated, and that would be only part of the cost of running her brand in today’s market.

On top of that would come the time and cost of brand ambassadorship, working with a distributor, negotiating with retailers for shelf space and more.

“One of the main things we keep running up against over and over and over again is none of the distributors really want to actually sell your brand,” Kornberg said.

“All of them have their own brand, and they would rather buy bulk from you, package it themselves and sell it under their brand rather than try to promote your brand.”

Yet another reason many Humboldt farmers have chosen wholesaling over branding has been changing packaging rules.

Moreover, the market is now saturated after many marijuana companies launched in 2018 and 2019.

That has kept Nik Erickson and his Humboldt company, Full Moon Farms, from jumping into branding.

“Right out of the gates, California didn’t know what to do, so they kept changing the regulations,” Erickson said. “People would try to get ahead of the curve and buy $100,00 worth of packaging, and then regulations change, and now … all their packaging is useless. That’s $100,000 down the tubes.

“We saw that, and we saw the explosion of brands, the market saturation, and we didn’t just want to just be caught up in the clutter. We knew there would be a contraction, and we’re seeing that right now.”

But this year and next, he said, Full Moon is experimenting with co-branding. In such a venture, which some distributors are trying out – the farm’s brand is intertwined with the distributor’s on packaging, giving both companies more market visibility with consumers.

Steffano said he’s looking into the same types of deals and is “distributor shopping” at the moment.

John Schroyer can be reached at johns@mjbizdaily.com